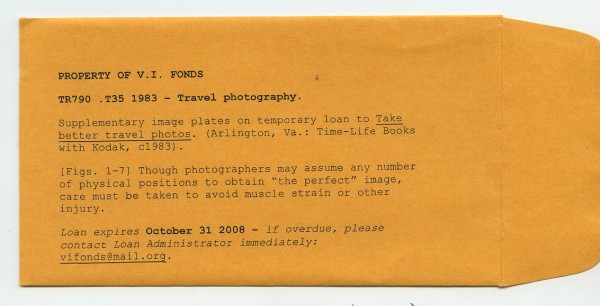

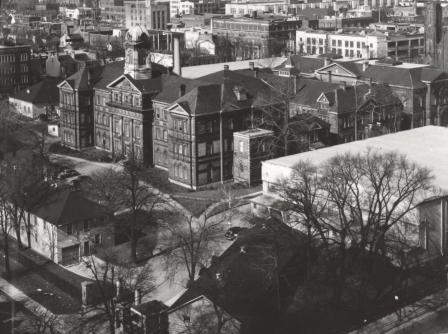

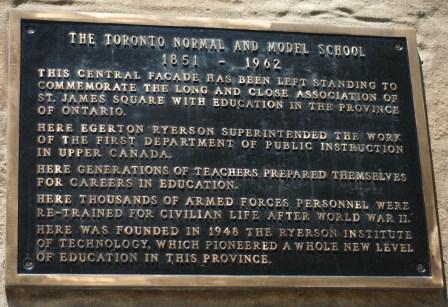

For the past few years at the Toronto Metropolitan University Library, mysterious photographs have been showing up in random library books. These photographs are housed in small paper envelopes that refer to them as “supplementary image plates” and label them “Property of V.I. Fonds”. Each envelope of ‘supplementary plates’ has ended up in a library book with a theme similar to the subject of the pictures within it. Only recently has the library solved the mystery of where these envelopes have been coming from.

It turns out that the planted photographs are the result of a project assigned by Image Arts Professor Vid Ingelevics to his Documentary Media MFA students for the course “Databases, Archives and the Virtual Experience of Art.” For the project, students were presented with an archive of 100 images on CD and asked to create a system to classify them. Past student Mark Laurie, who graduated from the program in 2010, chose to rely on the Dewey Decimal System and Library of Congress Subject headings to help categorize the disparate images.

The title of the project – “Supplementary plates: The V.I. Fonds distribution project” – describes Laurie’s decision for classifying the images through placing them into library books. Each individual photograph remains connected to the others in archival fashion by fonds, acknowledging the original source and organization of the images, in a group of 100 from Vid Ingelevics.

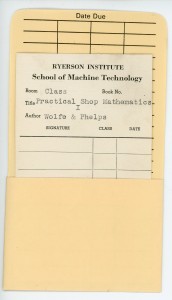

The artist printed the images as photographs, and divided them into library books because “without knowledge of the images’ provenances and the archival motivations behind their co-mingling, [Laurie] realized that by merely organizing them into batches, [he] could not hope to restore their meaning or significance.” Assigning each image, or small group of similar images, a Library of Congress Subject heading, Laurie searched the Ryerson Library catalogue and chose books with identical subject headings to place the photographs in. He used the Dewey Decimal and the Library of Congress Subject heading to complete the classification of his images, and placed them into books indicating that they were “on loan” from the V.I. Fonds to that book, adding to the Ryerson Library’s collection of images on that subject.

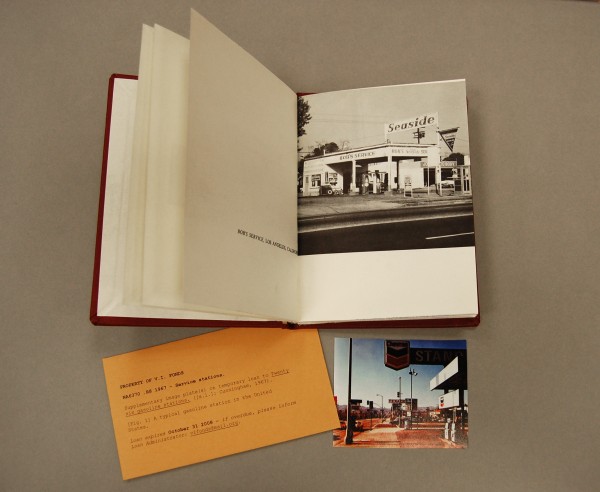

For example, Edward Ruschca’s book Twentysix Gasoline Stations was found with an envelope that reads:

PROPERTY OF V.I. FONDS

NA6370 .R8 1967 – Service stations.

Supplementary image plate(s) on temporary loan to Twentysix gasoline stations. ( [s.l. ]: Cunningham, 1967).

[Fig. 1] A typical gasoline station in the United States.

Loan expires October 31 2008 – if overdue, please inform Loan Administrator: vifonds@mail.org.

The envelop contained the photo of the gasoline station in the United States.

PROPERTY OF V.I. FONDS

NA6370 .R8 1967 – Service stations.

Supplementary image plate(s) on temporary loan to Twentysix gasoline stations. ( [s.l. ]: Cunningham, 1967).

[Fig. 1] A typical gasoline station in the United States.

Loan expires October 31 2008 – if overdue, please inform Loan Administrator: vifonds@mail.org.

The envelop contained the photo of the gasoline station in the United States.

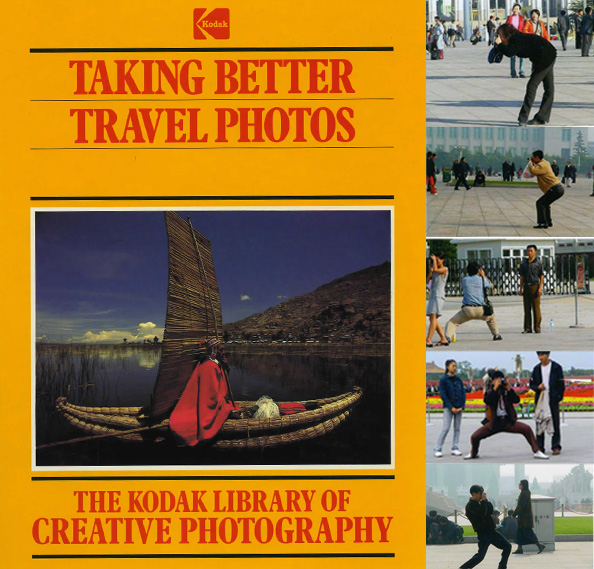

Other images that have been found include 7 photographs of people in the act of taking photographs in the book “Taking Better Travel Photos”, and a photograph of a group of friends dining together in the book “Dining Customs Around the World, with Occasional Recipes.”

The Ryerson Library is still on the lookout for more of these envelopes, so far only 28 out of 54 envelopes have been found. If you are interested in seeing those that have already been found, they are being held on the fourth floor of the library in Special Collections. You can help us with this mystery! If you happen to find one of the V.I. Fond envelopes, please bring it to the attention of library staff, so that we might add it to our collection.

Also hidden on our shelves…

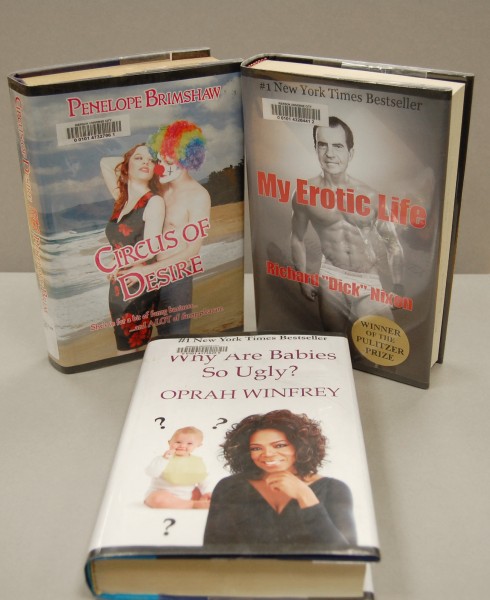

Staff at the Toronto Metropolitan University Library and Archives have also been surprised to find new titles added to our shelves throughout the past year. Donations to the library including books titled: “My Erotic Life: Richard “Dick” Nixon”; “Why Are Babies So Ugly?” by Oprah Winfrey; “Circus of Desire” by Penelope Brimshaw; and “Puppies for Africa” by Jeffrey Sachs were found, anonymously donated, throughout the library.

With a little research, Ryerson Library staff was able to find the culprits and credit the donations to The Marxist Nudist Taxidermy Club of Toronto. The MNT club celebrated April fools day last year (2012) by making some library visits. The Ryerson library was one of only five libraries in Toronto to which the club kindly donated books that can’t be found anywhere else. The library is still on alert for the two missing titles from the MNT Books Project collection…

– Cassandra Rowbotham, June 2013

Links and further information

For information about Ryerson Library Special Collections: https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/

For more information about the Toronto Metropolitan University graduate program in Documentary Media: http://www.ryerson.ca/graduate/documentarymedia/index.html

More information about Mark Laurie’s project can be found here: http://mlaurie.wordpress.com/2008/11/19/supplementary-plates-the-vi-fonds-distribution-project/

More information about The Marxist Nudist Taxidermy Club can be found here: http://www.mntclub.com/about/