In the age of social media there are many ways for news to be communicated. Faculty, staff, students, alumni, and the general public can find out what is going on around campus through Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and many other sources. How did Ryerson get the word out there before the internet and smart phones – let’s take a look.

University Media

Ryerson has had various departments and offices responsible for getting the official news out to the community and the public. The Office of Information Services, the Department of Community Relations, the Office of University Advancement, and now University Relations were/are responsible to spreading the official word of Ryerson.

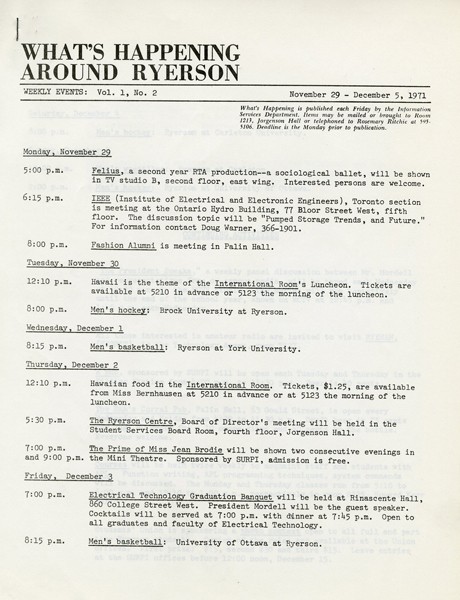

What’s Happening around Ryerson

What’s Happening around Ryerson (1971-1977) was published once a week as an events calendar by the Department of Information Services. It was replaced by On Campus this Week (1977-1986). The Office of University Advancement published Campus News (2004-2009) which was emailed out to the Ryerson Community announcing individual events, campus notes, and other related information. This was discontinued in 2009 with the creation of Ryerson Today. The Office of University Advancement, and now the Department of Communications, Government, and Community Engagement periodically send out news releases about significant Ryerson occurrences and events.

The FORUM newsletter

The FORUM was a newsletter of information and opinion first published by the Department of Information Services September 12, 1977. The FORUM continued to be published by the Department of Community Relations, and the Office of University Advancement changing styles and formats. It went to a digital only format in 2006 and continued on until 2009 when it too was replaced by Ryerson Today.

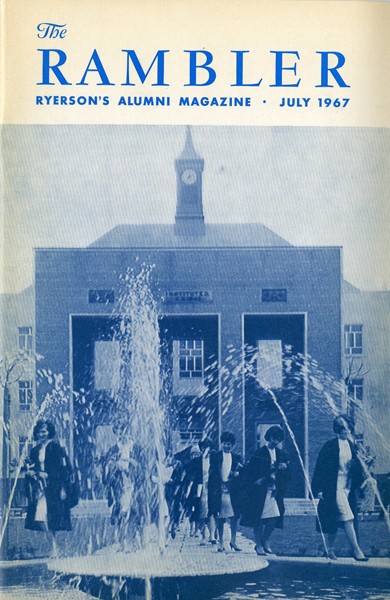

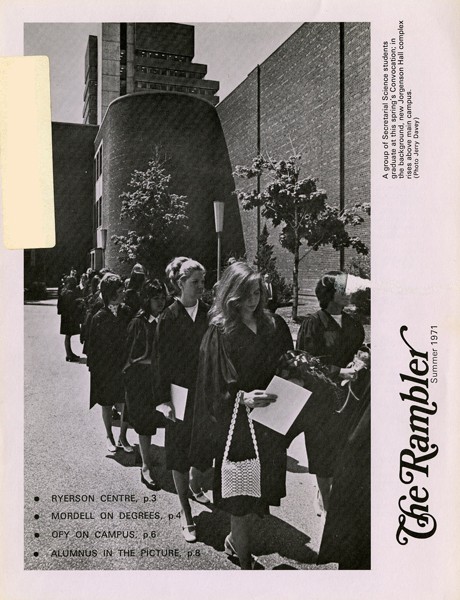

The Ryerson Rambler

The Ryerson Rambler (RG 151.01) was first published in June of 1962, was Ryerson’s alumni magazine. It was published initially by the Students’ Union. According to then Ryerson Principal Howard Kerr, “It is hoped in time that the Ryerson Alumni Association will be sufficiently strong to assume the responsibility involved in the financing of this project…”. It would appear that the Alumni Association took over publication in 1967. The Rambler continued publication until 1972, when it was replaced by Technikos as a source of information for Ryerson Alumni.

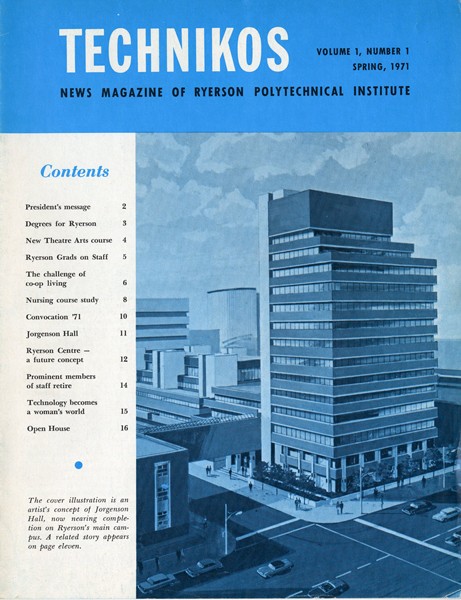

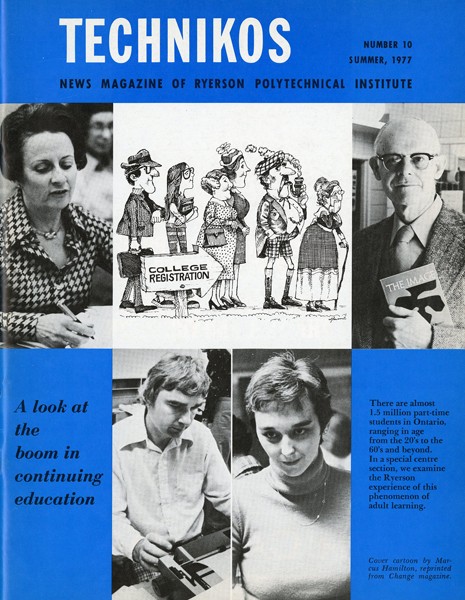

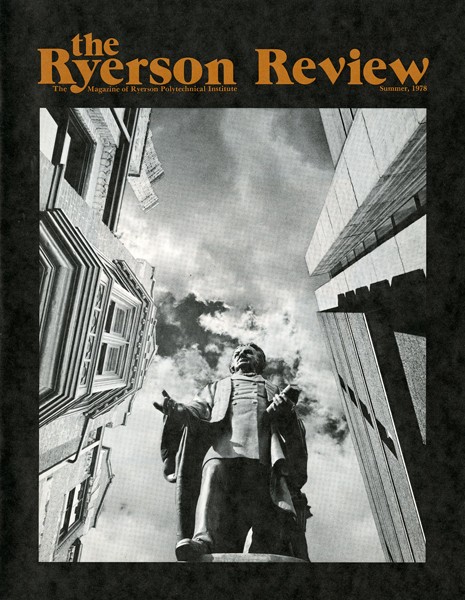

Technikos and Ryerson Review

Technikos the news magazine for Ryerson Polytechnical Institute was first published in the Spring of 1971 by the Department of Information Services and according to then Ryerson President “it would be mailed to the home address of each undergraduate…Copies will also be sent to potential employers…high schools, colleges, universities, and Ryerson alumni…”. It was published twice yearly until Summer 1977 when, according to the Ryerson Rambler, “…the costs have caught up with us and a quality magazine like Technikos cannot be produced economically enough to enable us to send it to you regularly…” so publication was cut down to one magazine per year sent out during the summer months. In 1978 the name was changed to The Ryerson Review. Its last publication was Summer 1980.

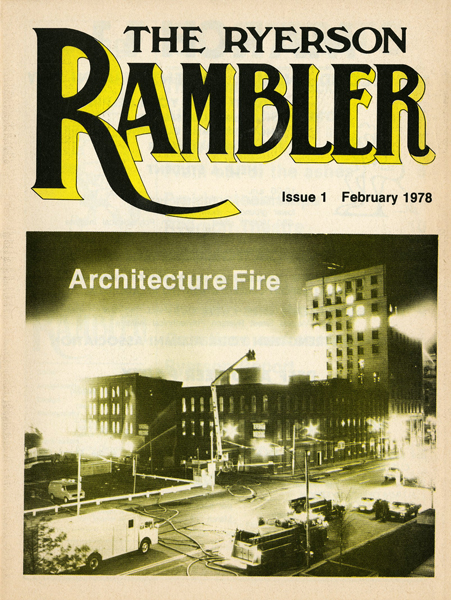

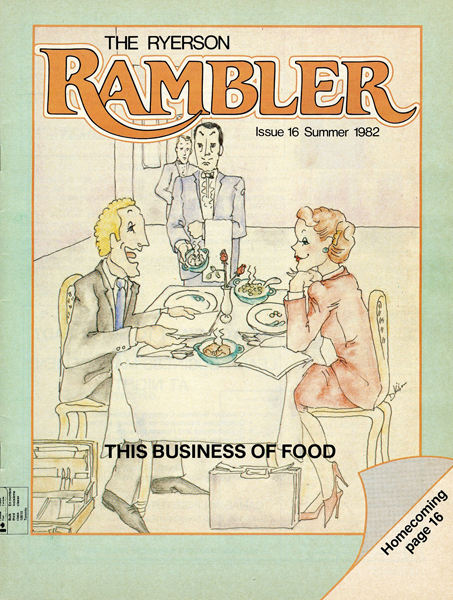

The Rambler redux

The Rambler returned in February of 1978 when the cost of producing Technikos became economically unfeasible. It was published 3 times per year. In 1994, the winter issue of the magazine was discontinued – replaced by What’s On, a newspaper-style newsletter. In 1997 they discontinued What’s On and started publishing the winter edition of the magazine again.

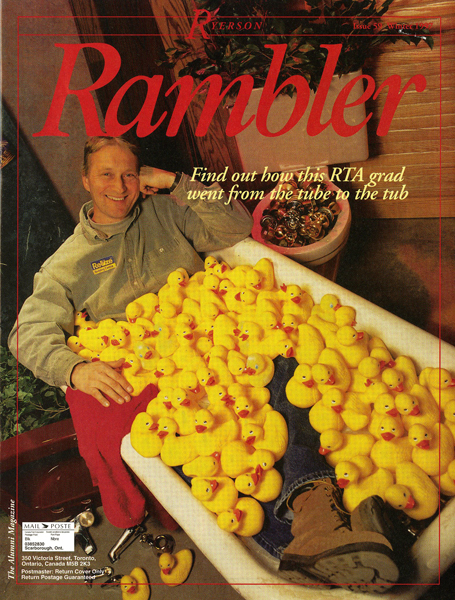

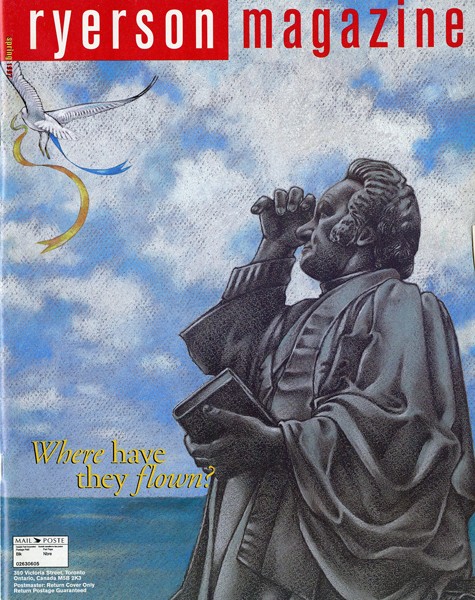

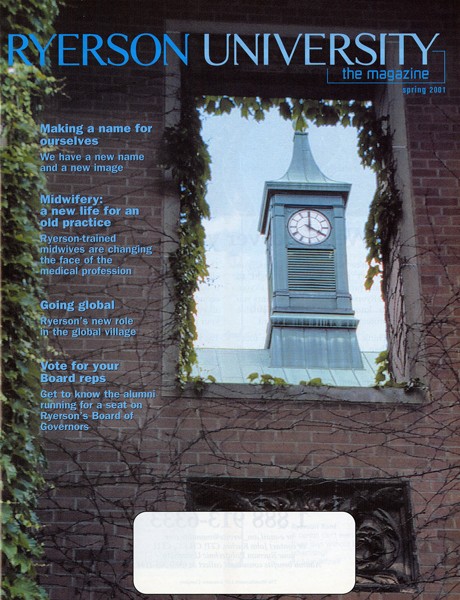

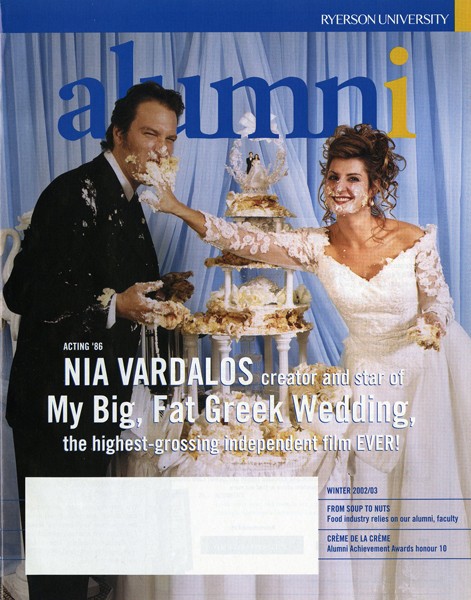

Ryerson Magazine

With the spring 1997 edition the name changed to Ryerson Magazine (RG 395.07.02)and began publishing only twice a year. In 2001, it changed its name to Ryerson University, the magazine – reflecting the name change of the University from Ryerson Polytechnic University to Ryerson University. It changed its name again in 2002 to Alumni Magazine, with a final name change in 2022 to Ryerson University Magazine.

Student Media

On the student side of the School, Ryerson has had student created publications since its inception in 1948.

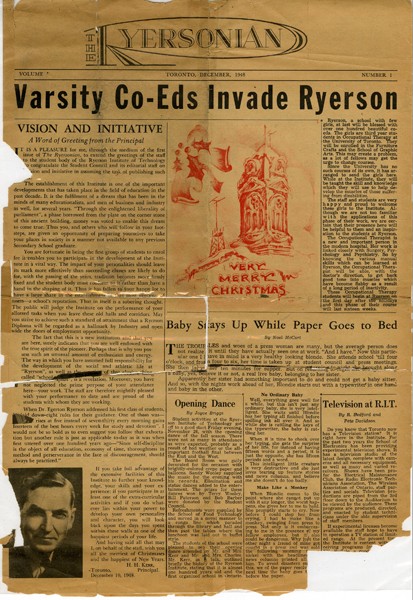

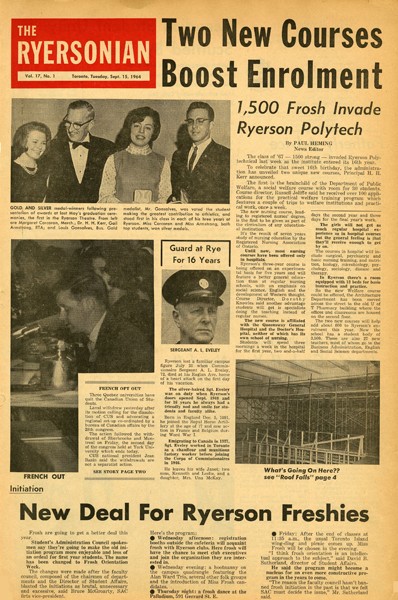

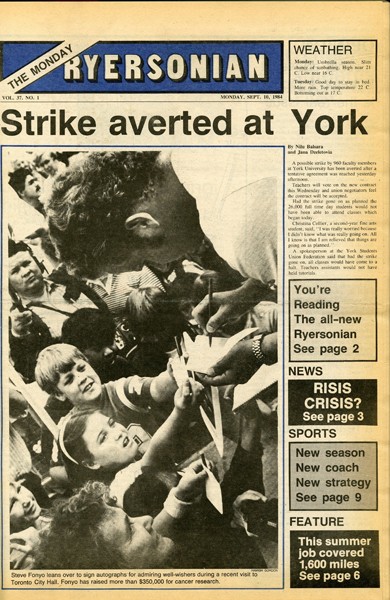

The Ryersonian

The School of Journalism began publishing a newspaper called the The Ryersonian (RG 95.05) in 1948. The first paper was published in December of that year. Starting in January of 1949 until April of 1951, the paper was published on a monthly or bi-monthly basis. In the 1951-1952 school year the paper began being published on a daily basis. It continued this way for many years, until they began publishing Tuesday – Friday, and then only on Wednesdays and Fridays. During the 1993-1994 school year it started its present schedule of weekly publication on Wednesdays. The paper is also available online at www.ryersonian.ca/.

Ryerson Daily News

In June of 1949, the School of Graphic Arts, and the Journalism program started printing Ryerson Daily News. It was a one page leaflet with Canadian and International news stories.

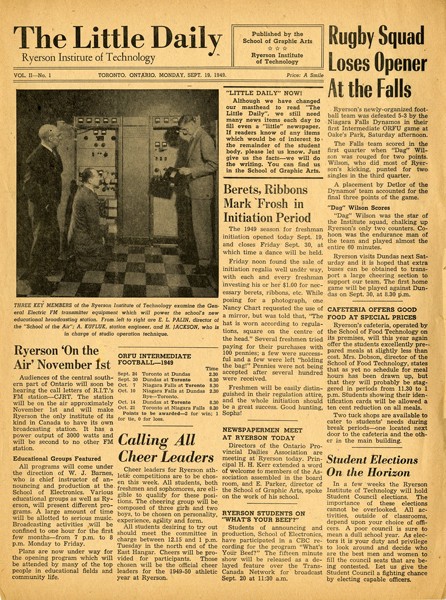

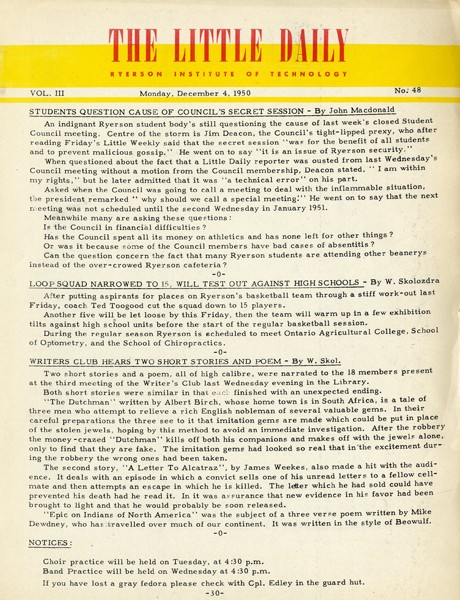

The Little Daily

It was replaced in September 1950 by The Little Daily. A one page information leaflet with news about Ryerson.

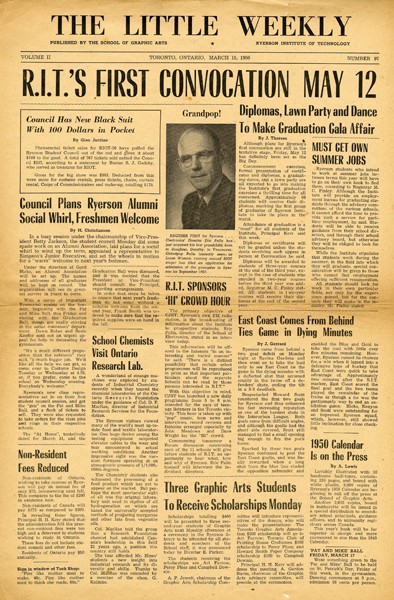

The Little Weekly

Starting in 1950 they also published the Little Weekly, a larger format newspaper style publication. Both the Daily and the Weekly ended publication in January of 1951.

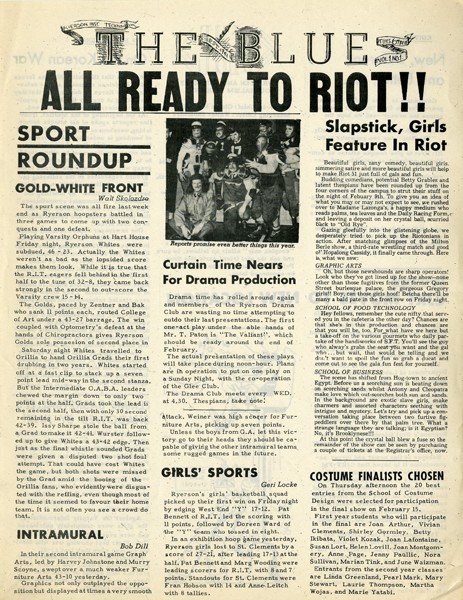

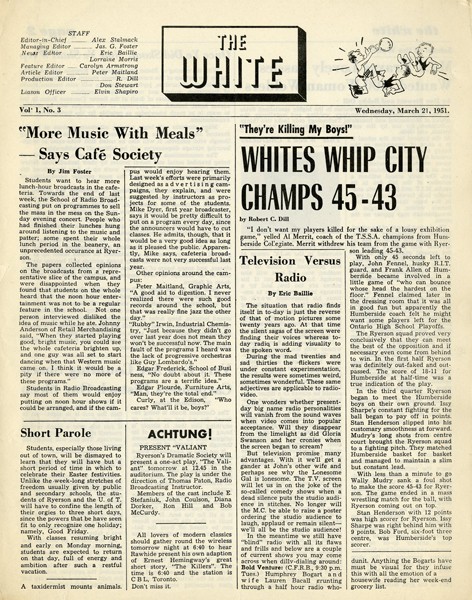

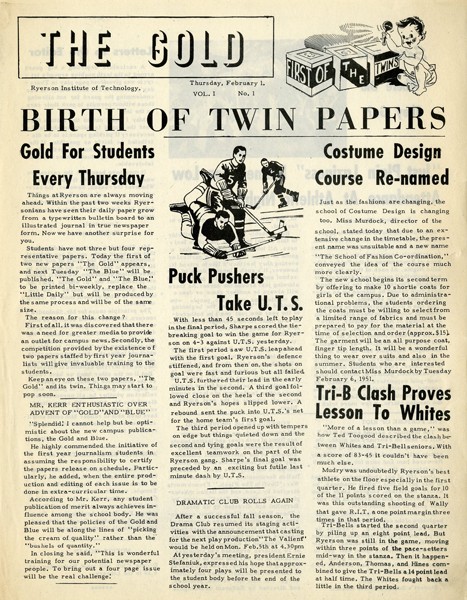

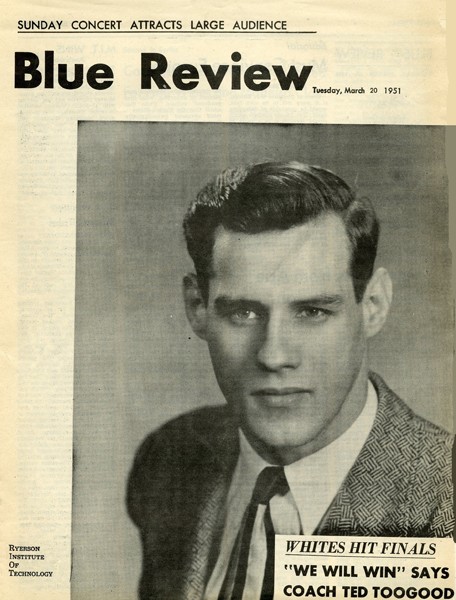

The Blue, The White, and the Gold

To replace The Little Weekly, Journalism students started printing three different small newspapers on three different days – The Blue (RG 95.31) on Tuesdays, The White (RG 95.28) on Wednesdays, and The Gold (RG 95.30) on Thursdays. They were produced between February and April of that year. In March and April of 1951 Journalism also printed The Blue Review (RG 95.33).

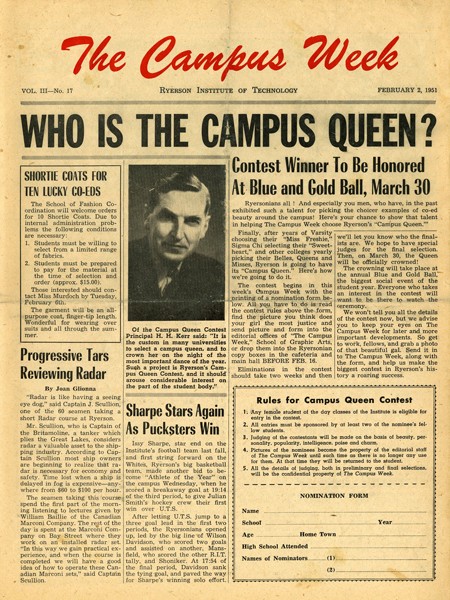

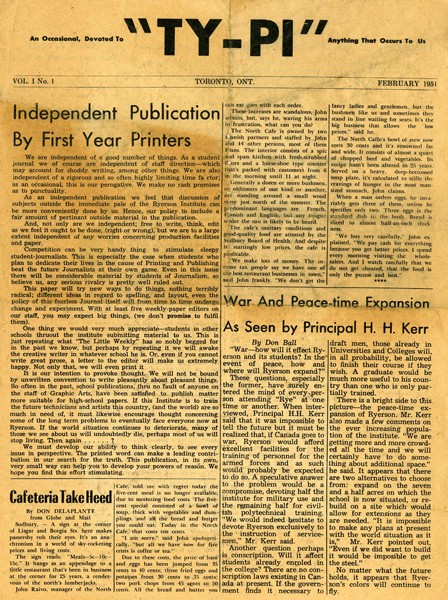

The Campus Week and TY-PI

The Campus Week also was created to replace the Little Weekly. First printed February 3, 1951, it was written and edited by Journalism students and printed by the the School of Graphic Arts. It had a four page format – mirroring that of The Ryersonian. It does not appear that this continued to be published in the 1951-1952 school year. There was an independent publication created in 1951 called “TY-PI”, created by first year students in the Graphic Arts and Journalism programs.

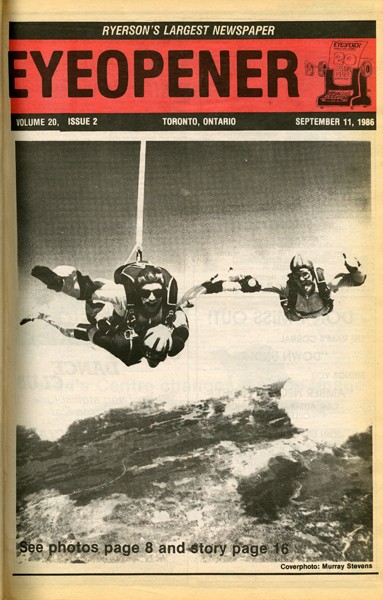

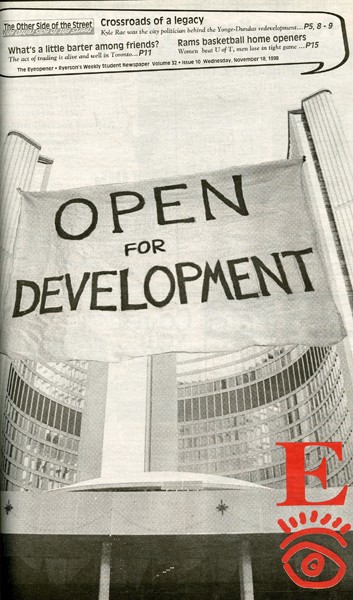

The Eyeopener

In 1967 the Eyeopener Newspaper (RG 146.1) – at first called the Eyeopener Magazine took its name from the Calgary Eye Opener, newspaper published by Bob Edwards 1902-1922. It was created because, as its first editor Tom Thorne stated, many students felt that the Ryersonian was not representative of all of Ryerson’s students. Published on Tuesdays by the Students’ Administrative Council on a weekly basis, it was a member of the Canadian University Press. During the 1968-1969 school year it began being publishing on Thursdays and starting in September 1990 it changed to its current schedule of publication on Wednesdays. The Eyeopener is available online at theeyeopener.com.

All of these publications contain valuable information about the life and times of Ryerson and its students, staff, and faculty. They have been an invaluable resource for many research projects.

They are available for viewing in Archives & Special Collections. Please call (416) 979-5000 ext. 7027 or email asc@ryerson.ca for an appointment.