We’re joining the Archives of Ontario in their #ArchivesAtoZ month-long campaign. The aim is to increase the public’s awareness of archives and their collections. We’ll be sharing four blog posts throughout the month showcasing items from our collections and demystifying archival concepts related to each letter of the alphabet.

- April 4: A to F

- April 11: G to M

- April 18: N to S

- April 25: T to Z

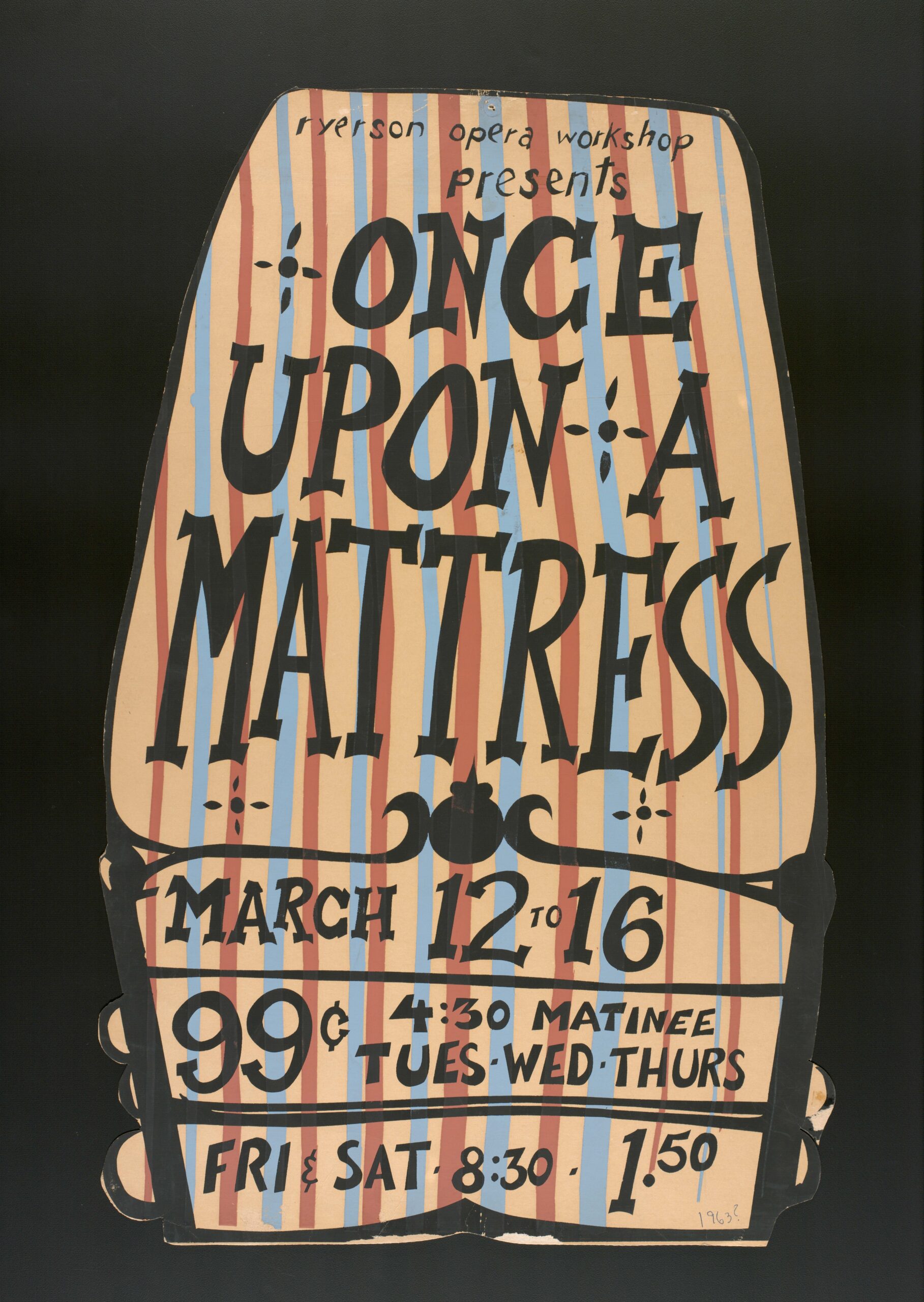

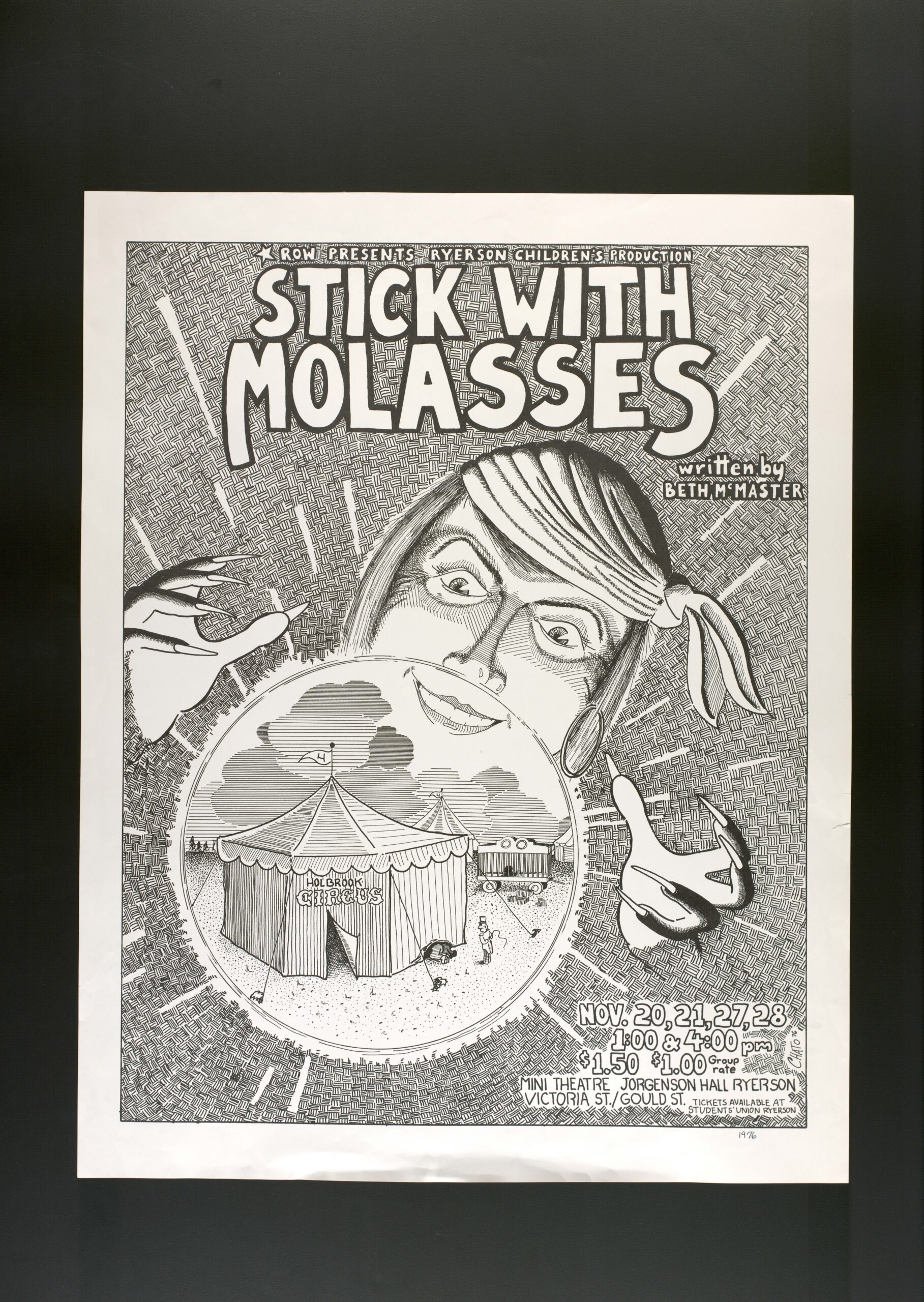

Graphic Materials

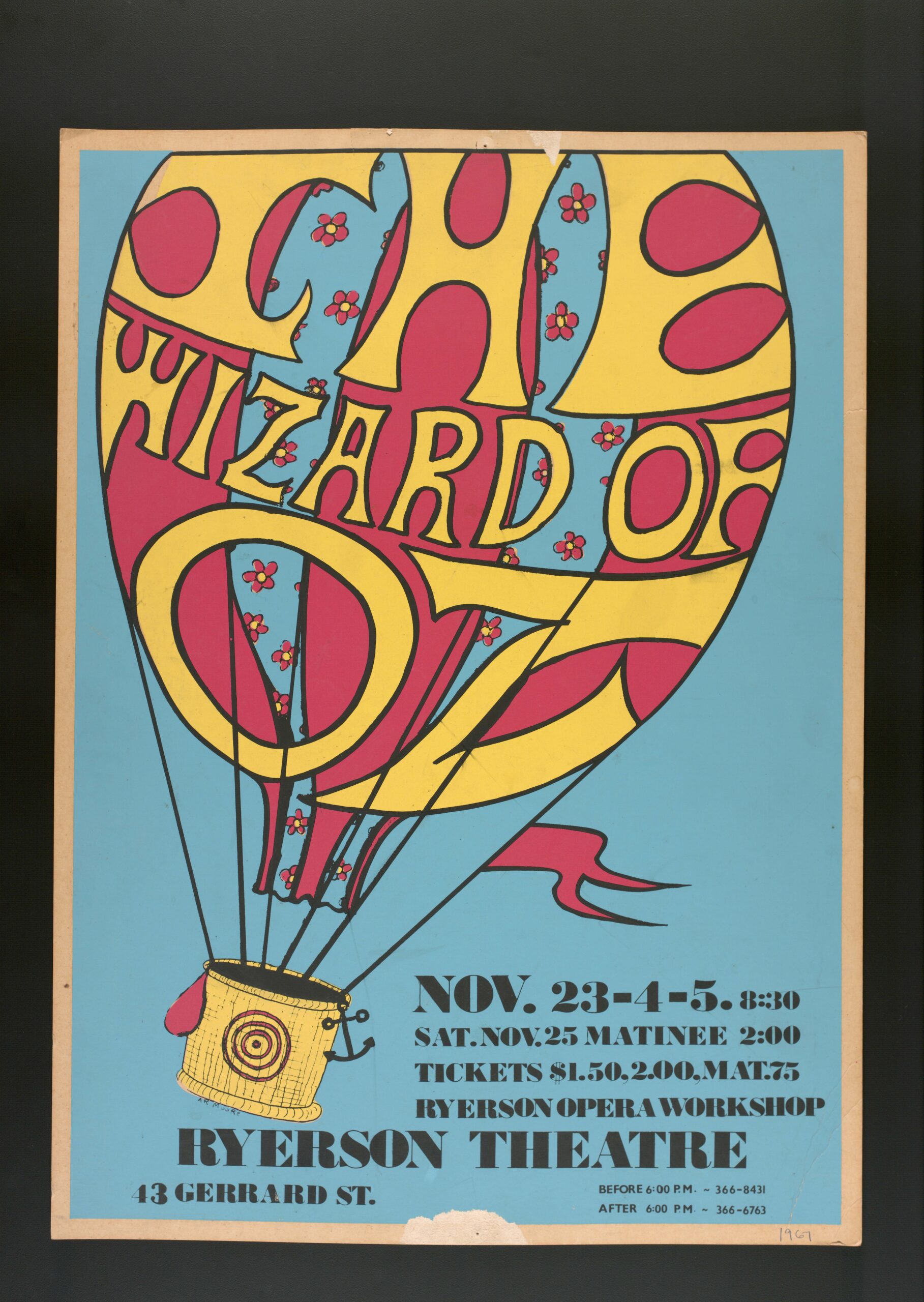

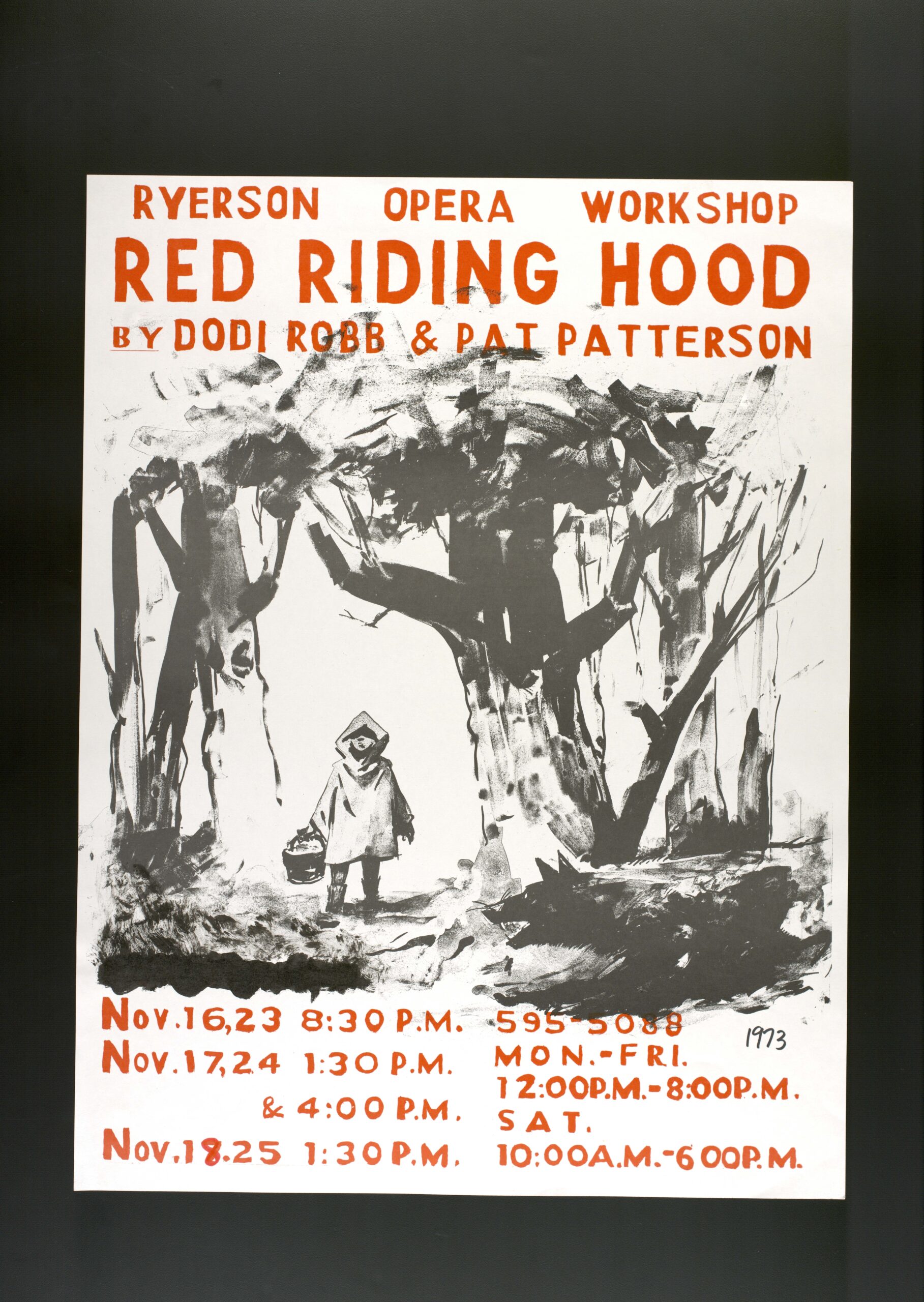

According to the Canadian Council of Archives graphic materials are “…are defined as documents in the form of pictures, photographs, drawings, watercolours, prints, and other forms of two-dimensional pictorial representations.” This definition includes a diverse range of materials and processes that often make up the bulk of an Archives or Special Collections holdings. While conducting research last year – we came across these amazing hand painted and hand drawn theatrical posters created by students to advertise Ryerson Opera Workshop productions. The Ryerson Opera Workshop, or ROW, was established in 1951 by Jack McAllister, at the time faculty in the English Department and would later be one on the founding faculty in the School of Performance. The workshop was an institute-wide, student endeavour from production crew to cast members.

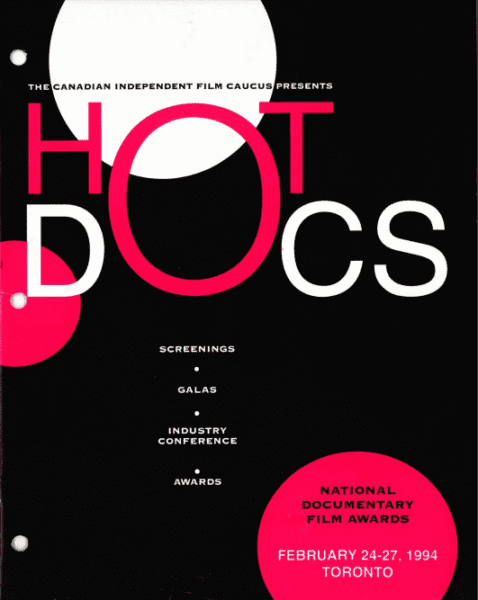

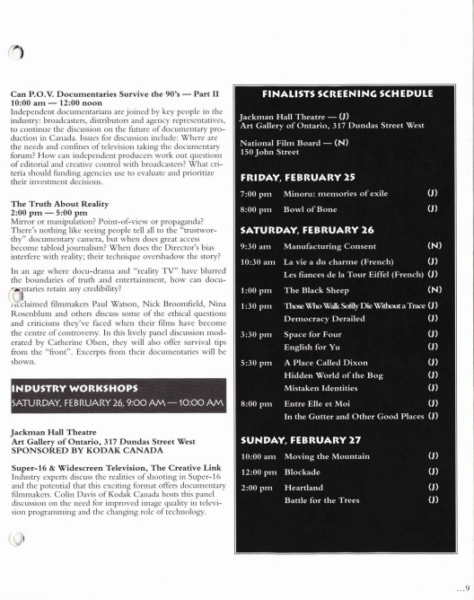

Hot Docs

The Hot Docs Fonds includes physical and digital material produced for the annual Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival. Digital copies of the programs from 1994 to 2001 festivals can be viewed on our database by clicking on the program’s cover images. We’re looking forward to this year’s festival, which begin on April 28th !

Imaging

Imaging, also known as digital imaging, reformatting, scanning or digitizing, refers to creating an electronic representation of an analogue object. The are several standards for imaging cultural heritage material, such as the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative (FADGI) and the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN).

We generally use a flatbed scanner for graphic material, and an overhead copy stand for large prints and 3-D objects. We also digitize audiovisual formats such as VHS tapes and audio-cassettes, since they tend to deteriorate quickly and the playback equipment required for reformatting is becoming less readily available (a tape deck or a VCR for instance.)

We often get asked why libraries and archives can’t digitize all of our collections for online access! The Peel Art Gallery Museum + Archive has a blog post with great answers to this question, but it generally is tied to the amount of resources required for mass digitization (staff time, technical equipment, digital storage, copyright clearance, etc.) Take a look at what we’ve digitized so far through our online database!

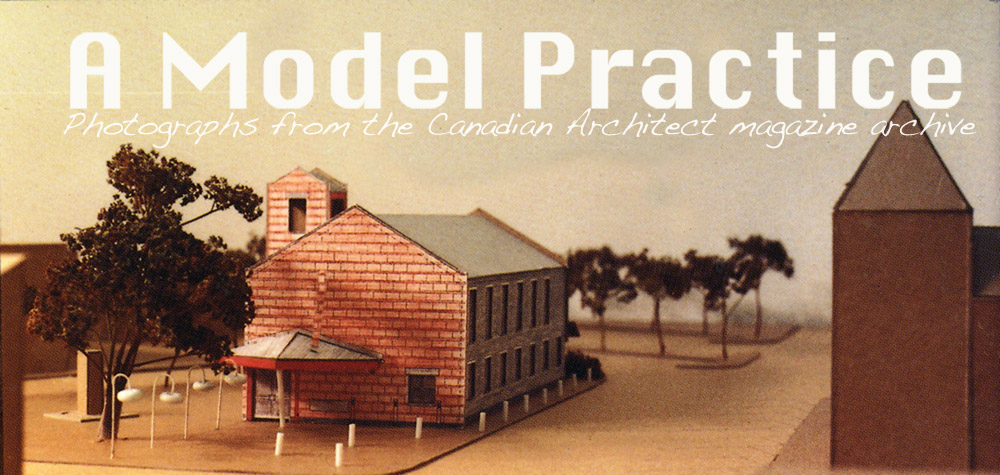

Jorgenson Hall Model

The Jorgenson Hall/Podium/Library Building architectural model is one of three campus building models in our collections (the other two being Pitman Hall and the RAC). This one was created by Webb Zerafa Menkes Housden Architects Engineers and shows the three buildings plus the west side of Kerr Hall which attaches to the complex via footbridges at either end.

Keyword Searching

Keyword searching can be hit and miss when it comes to looking for archival records – especially if you are starting your research in an internet search engine. Every search comes back with hundreds of thousands of returns – so how do you improve your chances of finding what you are looking for?

Having a plan of action that includes an initial list of keywords is a good way to start. When thinking of what keywords you want to use there are several things to keep in mind:

- 1) The age of the records you are looking for and the time period of their creation – terminology is ever evolving and you may find your search returns include offensive and outdated terminology that is no longer in use, but would have been at the time of the records creation

- 2) Word spelling – countries may spell words differently so include all the potential spellings of your keywords when you are searching.

- 3) Alternate/previous names – this is especially important if you are researching a geographic location – has it always been called what it is named now?

Finally – consider adding some of these terms to the end of your keywords: papers, photographs, collections, exhibition, primary source, archives, special collections, library, museum, curriculum. Any or all of these terms may help narrow down your search and help you find what you are looking for. Robin M. Katz’s “How to Google for Primary Sources” has some other suggestions to help you with your search.

Lorne Shields

Lorne Shields has been an avid collector of bicycles and bicycle ephemera since 1967. His passion for bicycles led him to collect photographs on the subject as well as books, magazines, and bicycle memorabilia.

Shields donated his collection of photographs unrelated to bicycles to Special Collections in 2008. This includes studio portraits and carte-de-visites as well as landscape and industrial imagery from the Victorian era to the 1960s. The collection also comprises many vernacular photographic albums, good examples of glass and metal photographic processes including cased daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes. Explore our database for more information on the Lorne Shields Historical Photograph Collection.

![2008.001.1872 - [Portrait of three women], image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2008_001_1872-514x600.jpg)

Miniature Cameras

Did you know we have several miniature and sub-miniature cameras in the collection? These mini photo devices are designed to take photographs on film sized smaller than 135 format (24mm x 36mm). The Minolta-16 camera seen below takes 10×14 mm exposures on 16 mm film.

Miniature cameras gained a reputation as “spy” cameras, and while some of the higher quality ones (including the Minox) were used by government agencies, most were simply for amateur use.

Next week we’ll highlight items and archival concepts for the letters N to S!