The idea for this blog started in the summer of 2022 when I was brainstorming ideas for interesting ways to showcase our collections. I started looking through the Bass Stereographic Photography Collection and was intrigued by these three cards because I wasn’t familiar with them or where they might be located. Originally intending the blog to be a simple show and tell of interesting images around Toronto, it quickly evolved into a more in-depth project using the stereographs as the starting point for my search – a kind of showcase of how archival and special collections materials can be used to spark new ideas or enhance existing research projects.

Utilizing both online resources, and books from the TMU library collections – I was able to not only pinpoint the locations of the subjects in the photographs, but the history of the sites as well. There is a full bibliography available at the end of the blog.

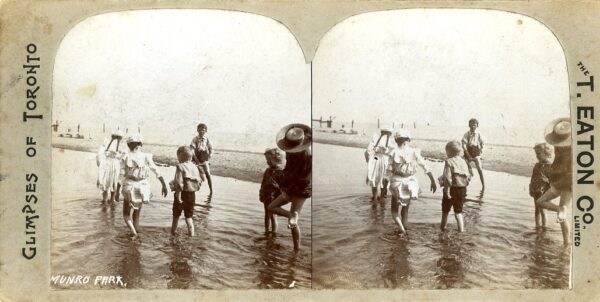

Munro Park

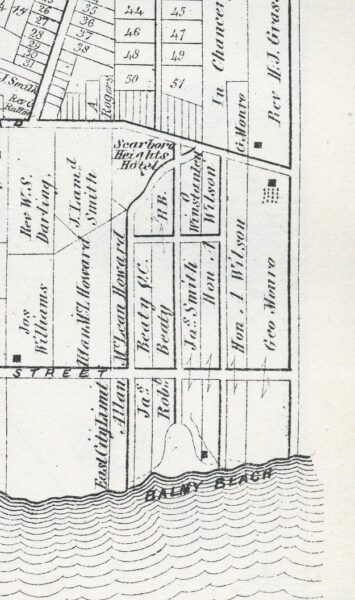

In 1847 former Toronto Mayor and business man George Monro (1797-1878) purchased 60.5 acres of Lot 1 Concession 1 in Toronto. In present day terms the property, called Painted Post Farm, was bordered by the lake in the south, Scarborough Road in the west, Kingston Road in the north and Victoria Park in the East.

The properties to the east and west of Painted Post Farm were slowly being developed into summer resort and recreation areas and in 1896 Monro’s family granted a 10 year lease to the Toronto Railway Company (TRC) for a portion of their property. The section, which consisted of the bottom portion south of Queen Street East down to the lake, was leased by the TRC for the purpose building an amusement park which would be serviced by their electric trolley cars. At the time of the lease their tracks, which ran along Queen Street East, stopped at Balsam Avenue (3 streets east of the Monro property). In 1896 Munro Park (it is unclear when the spelling changed from Monro to Munro) was initially opened as a picnic area, with 50 benches and 100 seats, A large 1300 square metre dance hall, a bandstand, and some rides – carousel, swings – were added in the first season and in 1897 a mineral well was opened. By 1898 the street car tracks were run in a loop to the park and a ferris wheel was constructed. In 1899 a water carousel, Lundy’s Ostrich Farm, and two 90 metre boardwalks leading to the entrance of the dance hall were added. More sidewalks were created and the size of the performance stage was increased, with seating for 5000. The TRC began booking performers including acrobats, animal acts, comedians, magicians, musical performers, vaudeville and minstrel shows. They also added a motion picture venue in 1900.

Courtesy of the Baldwin Collection of Canadiana, Toronto Public Library

In 1906 the lease with the TRC was not renewed and all the buildings were removed from the property. The following year Scarboro Beach Park, just a few blocks from Munro Park, opened and it was purchased by the TRC in 1912. In the 1920’s the TRC became one of the two companies, along with Toronto Civic Railway, that became the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). The Monro property and Munro park were later subdivided for residential development and nothing of the old park exists. A street, Munro Park Avenue, runs through the centre of the old park property and the shoreline is now part of Silver Birch Beach.

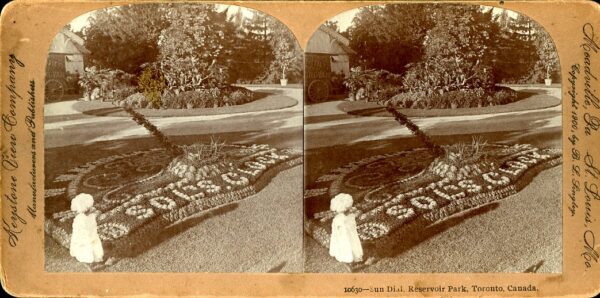

Rosehill Reservoir

Reservoir Park, located in Toronto’s Deer Park neighbourhood, opened in 1874. The land it sits on is one of the city’s oldest public recreational spaces. But the area has a much older pre-colonial history. The area, called “Mishkodae” or prairie/meadow in Anishinaabemowin, was used for hunting by the Indigenous peoples. The lands open savannah like environment attracted the deer to feed. The area was also rich in plants that were harvested for use in medicines.

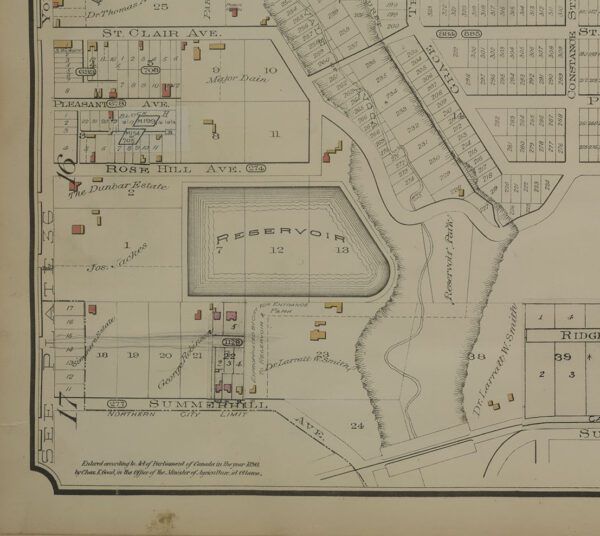

The reservoir and surrounding lands were part of two 200 acre lots that fronted on to Yonge Street between Summerhill and St. Clair Avenues. Lot 16 was purchased by Walter Rose who constructed a house, called Rose Hill, in 1836. The neighbouring property, lot 17, was purchased by Charles Thompson and a house “Summerhill” was constructed on the property in 1842. In 1853 Thompson developed some of his property into an amusement park with swings, landscaped gardens, and paths leading down into the Ravine. The park was referred to as Thompson’s Park, but he changed the name to Summer Hill Spring Park and Pleasure Grounds.

In 1865 Walter Rose died and his property was subdivided and sold. Some of the property was purchased by Joseph Jackes and Richard Dunbar. Thompsons property was sold to Larratt Smith in 1866. In the early 1870’s the city hired consultants E. S. Chesborough and T. C. Keefer to design a waterworks system. They recommended a site north of the city for the construction of a reservoir. In 1872 the city purchased sections of property from Jackes, Dunbar, and Smith for the reservoir. Smith’s sale was contingent upon the city’s maintaining his section of property as the parkland it already was. The reservoir itself would be constructed on the Rose Hill property. In October of 1873 the construction contract was awarded to R. Mitchell and Co. and construction was completed in December of 1874 – named the Rose Hill Reservoir for the property it sat upon. The reservoir could hold 126 million litres of water and was connected to the John Street pumping station 8 kilometres away.

4 November 1942. Item 2014, Subseries 72, Series 372. Fonds 200 Former City of Toronto fonds. City of Toronto Archives.

After its construction Reservoir park was a popular attraction with its access to the Vale of Avoca/Yellow Creek Ravine. The reservoir, considered the community’s lake, was closed to the public during World War I to protect the water supply. This was done again for World War II – with a fence being erected in 1940. After the war was over the fence was left in place to help protect against water contamination. In 1949 the city began considering covering the site because of the pollution from birds, dogs, and people. Fish were found to be swimming in the reservoir at one point. In 1960 the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto commissioned consulting engineers Gore & Storrie Ltd to plan for an expansion and covering of the reservoir to much protest of the local community who didn’t want to lose their lake. The renovation project (1964-1966) cost $3.4 million dollars and increased the reservoir to 270 million litres. A water fountain, reflecting pools, waterfall and other water features were added to the new landscape to make up for the loss of the lake.

Reservoir Park became part of the larger present day David Balfour Park whose entrance is located at 75 Rosehill avenue and is now a 20.5 hectare park. A major renovation was completed in 2022 with work on both the reservoir and its surrounding park. Accessible, multiple use trails, new lighting, and an expanded community garden were added.

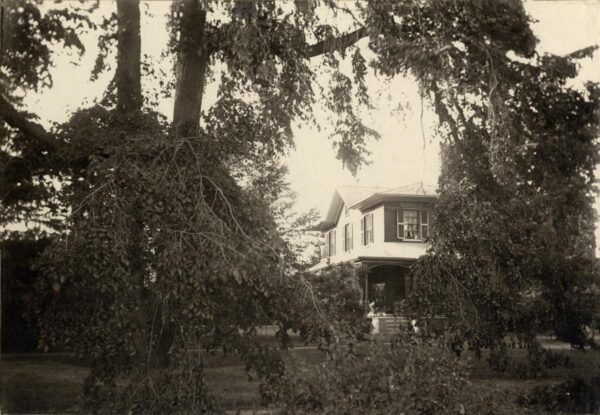

Government House

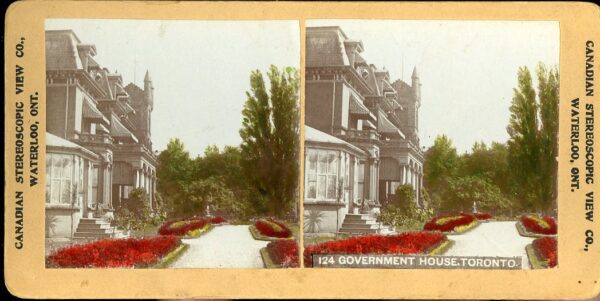

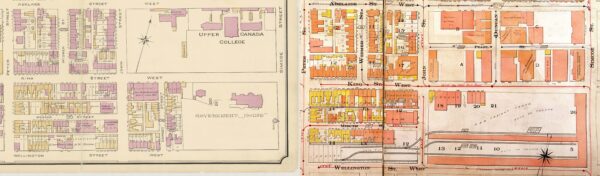

Government House was the name for the official residence of the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada and Ontario – a tradition which ended in 1937 with the closing of the final residence Chorley Park. Between 1792-1937 there were 9 homes used by the Lieutenant-Governor, none of which are still in existence today.

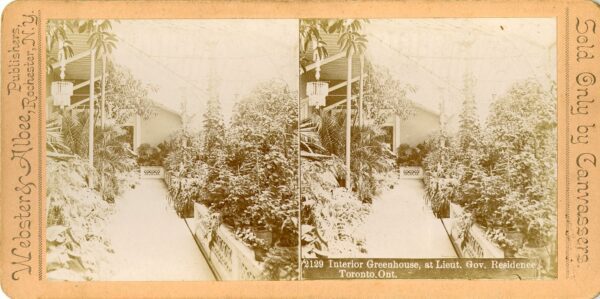

The Government House featured in these stereocards was the 7th home – is known as Old Government House. Located on property at King and Simcoe Sts (where Roy Thompson Hall and Metro Hall currently stand) the house was designed by architect Henry Langley of Gundry and Langley and constructed by Grant & York of Peterborough. The three storey red brick and ohio cut stone home featured galvanized iron cornices and a mansard roof. The main entrance faced Simcoe Street and featured a covered carriage entrance featuring a 100 foot tower. The main building was three storeys above a basement level, with the kitchen wing only 2 storeys. It also had a large glassed conservatory which opened off of the dining room. The house completed construction in 1870, with the John Beverley Robinson, the 5th Lieutenant-Governor for Ontario, being the first to reside there.

The house cost $102,000 dollars to build and was paid for with government money. Its construction was not without critics – many not seeing the need for a whole residence for the Lieutenant-Governor to live in, when offices and sitting rooms in the legislature could be provided at a much lower cost. An article in the January 6 1869 Globe newspaper pointed out “Very little is said in any quarter in defence of the lavish expenditure being made upon the residence of the Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario…the prospect is that the Governor’s residence in Toronto will be, all circumstances considered, more expensive than Rideau Hall at Ottawa.” The article continues on to discuss the considerably less amount of funds being spent on hospitals.

In 1910 the area where Old Government House was located was becoming increasingly commercial and industrial. The Canadian Pacific Railway (C. P. R.) began purchasing lands adjacent to the house. It was felt that a new residence was needed and property in north Rosedale was purchased. In the April 18, 1910 edition of the Toronto Star the Ontario Government put a legal notice: “Tenders for Government House property…up the first day of June 1910 for the purchase of property known as Government House property situate at south-west corner of King and Simcoe Sts…containing 6.19 acres…the buildings on the said property consist of a three storey residence, coach house, stables, gardener’s house, gate lodge, conservatories and greenhouses.”

The property was purchased for $800,000 by the C. P. R in June with the Lieutenant-Governor staying in residence while the new house was constructed. Unfortunately in March of 1912 the C. P. R. requested that the residence be vacated so they could begin developing parts of the property. A temporary residence was located for the Lieutenant Governor – Pendarves House (now Cumberland House) at College and St. George Sts. was rented until Chorley Park was completed in 1915. Lurie and Company wreckers purchased Government House, demolishing the building and selling off materials for use in other construction projects. Demolition began in June of 1912 and was completed in August of that same year. The C. P. R. used the space for a railway yard.

https://www.toronto.ca/ext/archives/goads_atlases/1910_1923_v1/g1910_1923_pl0005.jpg

The Bass Stereographic Photography Collection was donated to the University Archives and Special Collection by Gail Bass in 2018. The items were collected by the late Dr. Martin J. Bass and Gail Silverman Bass and included approximately 8000 stereograph cards – including 800 cards showing scenery, buildings, and landmarks from across Canada.

Bibliography

City of Toronto Archives “What’s Online” https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accountability-operations-customer-service/access-city-information-or-records/city-of-toronto-archives/whats-online/

Toronto Public Library Digital Archive https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/

Toronto Public Library Local History & Genealogy https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/history-genealogy/

Munro Park

Illustrated Historical Atlas of the County of York and the Township of West Gwillimbury and Town of Bradford in the County of Simcoe, Ont. Mika Silk Screening, 1972.

Morgan, Wayne. “Munro Park/East Beach City of Toronto Heritage Conservation District Study and Plan.” City of Toronto, 2008, www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2009/pb/bgrd/backgroundfile-18277.pdf.

“Munro Park (1896-1906).” The Coaster Enthusiasts of Canada – Closed Canadian Parks – Ontario – Scarborough, www.cec.chebucto.org/ClosPark/Munro.html. Accessed 6 July 2023.

“TO Built Walking Tour: The Beaches.” Architectural Conservancy Ontario, www.acotoronto.ca/res_files/TOBuilt-Walking-Tour_Beaches.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Rosehill Reservoir

“3 Places Where You Can Discover Toronto’s Indigenous History | CBC News.” CBC News, 21 June 2017, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/first-story-toronto-indigenous-history-1.4170290.

Atlas of the City of Toronto and Vicinity, March 1890, revised September 1903. Library and Archives Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3836028&lang=eng

Brown+Storey Architects Inc. (2016, June 6). Rosehill Reservoir, Toronto Heritage Impact Assessment. https://www.brownandstorey.com/content/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Rosehill-Reservoir-HIA-Draft-Final-20160606-reduced.pdf

Kinsella, Joan C. Historical Walking Tour of Deer Park. Toronto Public Library, 1996. https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/336600#

Robertson, J. Ross. “Robertson’s Landmarks of Toronto : A Collection of Historical Sketches of the Old Town of York, from 1792 until 1837, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1908.” Internet Archive, 1 Jan. 1970, archive.org/details/landmarkstoronto05robeuoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

“Rosehill Reservoir.” Lost Rivers Walks, www.lostrivers.ca/points/Rosehill_Reservoir.htm#:~:text=Built%20in%201873%2674%20with%20a,was%20constructed%20on%20its%20roof. Accessed 13 July 2023.

Rosehill Reservoir Rehabilitation (2022, November 9). City of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/community-people/get-involved/public-consultations/infrastructure-projects/rosehill/

Toronto Parks, Forestry and Recreation. “David A. Balfour Park.” City of Toronto, 6 Mar. 2017, www.toronto.ca/data/parks/prd/facilities/complex/143/index.html.

Government House

“Fine stained window lost to the province”. The Toronto Star. 25 June 1912. pp. 1 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/page-1/docview/1432739672/se-2.

Forsyth, Grant, Mrs. “Memories of Government House: passing of a famous social shrine.” The Globe (1844-1936). April 27, 1912. pp. A2, A7 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/memories-government-house-passing-famous-social/docview/1316227696/se-2.

“Gallery 1793-1815: Fort York Government House, 1800. Library & Archives Canada, C-16016.” Friends of Fort York , www.fortyork.ca/29-gallery/103-gallery-17931815.html#!1800_Fort_York_Government_House. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Gross, P. (1877). Illustrated Toronto, past and present. Canadiana. https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.24893/1

“Lieutenant-Governor obliged to vacate: C. P. R. wants possession of a portion of old government house property.” The Globe (1844-1936), March 2, 1912, pp. 9. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/lieutenant-governor-obliged-vacate/docview/1324238400/se-2.

Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada. “Fort George National Historic Site – Navy Hall.” Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada, 25 May 2023, www.pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/on/fortgeorge/.

“Pendarves – Cumberland House.” Ontario Heritage Trust, heritagetrust.on.ca/pages/programs/provincial-plaque-program/provincial-plaque-background-papers/pendarves-cumberland-house. Accessed 10 Aug. 2023.

“Provincial Plaque Background Papers: Pendarves-Cumberland House.” Ontario Heritage Trust, www.heritagetrust.on.ca/pages/programs/provincial-plaque-program/provincial-plaque-background-papers. Accessed 3 Aug. 2023.

Previous government houses. Lieutenant Governor of Ontario. (2017, June 14). https://www.lgontario.ca/en/tours/previous-government-houses/

“Separate depots for the railways – rumour that it is the C. P. R. which is buying land in Wellington Street”. The Toronto Star. January 4, 1910. pp. 1 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/page-1/docview/1435964760/se-2.

“Some bold biffs at Government”. The Toronto Star. February 9, 1910. pp. 7 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/page-7/docview/1431991356/se-2.

“Tenders for Government House Property”. The Toronto Star. April 18, 1910. pp. 6 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/page-6/docview/1436256066/se-2.

“The C. P. R. gets the Government House”. The Toronto Star. June 7, 1910. pp. 6 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/page-6/docview/1436270790/se-2.

“The Governor’s Residence”. The Globe (1844-1936). January 6, 1869. pp. 2 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/governors-residence/docview/1518970923/se-2.

“The Lieutenant Governor’s Residence”. The Globe (1844-1936). June 29, 1868. pp. 2 ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.torontomu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/lieutenant-governors-residence/docview/1518951434/se-2.