T’was a dark and stormy night… After a lovely roast dinner with your extended family, you all settle around a cozy fire in the parlor, sipping digestifs and listening intently as the older members of your family reminisce about times long gone by. Happy stories, sad stories, tales of love and loss… You are snapped out of your dreamy daze when your grandmother places her slender fingers on your shoulder.

“Do you mind grabbing some boxes from the cellar, dear? I’d love to show everyone your grandfather’s old motorcycle. Oh! And that house we had on the cul-de-sac.” Ear-splitting thunder startles you further, but you softly nod and get up from the couch.

You push the basement door open and it whines loudly, as if in protest of your actions. You are unsure of the last time anyone has stepped foot in the unfinished basement, and the cobwebs and smell of mildew are not encouraging. You pad down the stairs and approach a box labelled “photos and film.” The pen strokes are fuzzy from years of humidity and water stains are visible almost half way up the box. You open it up to ensure its contents, but something hits you, the sour and offensive stench of vinegar. The hairs on the back of your neck stand up as you reach to pick up a stack of film negatives. Frightening shades of bright blue meet your eyes, deep ridges in the delicate negatives threaten to split from your touch, emulsion adheres to emulsion, and the figures captured in each photo have faded beyond recognition. You gasp loudly and drop the stack of negatives back into the box. How could this happen? Decades of images, beautiful moments frozen in time, quietly lost to the standard environment of a damp basement. How could this happen?

What is vinegar syndrome?

Cellulose acetate film began to be widely used by 1952 after Kodak completed a four year long conversion program to replace nitrocellulose (nitrate) film which is known for its extreme flammability. Acetate film can be identified by the words “safety” printed along the edge of the film, dating information that matches with its advent, or destructive tests such as the float or burn test. Unlike nitrate film, the chemical composition of acetate film allows it to melt instead of burn, however, it is this composition that ultimately leads to its often unexpected demise. The chemical reaction that leads to the deterioration of acetate film begins when the acetate ions are exposed to moisture and heat which produces acetic acid, also know as vinegar. This reaction is “autocatalytic,” meaning it feeds on itself, cannot be stopped once it has started, and will speed up over time. Library and Archives Canada represents the deterioration of acetate film from vinegar syndrome in six distinct stages:

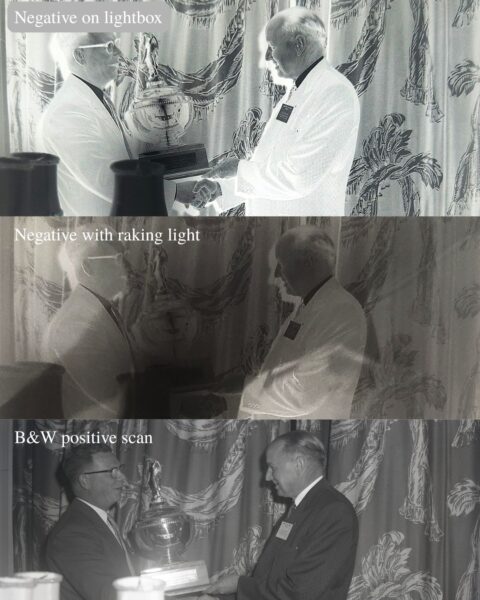

Stage one, where vinegar syndrome can not be detected without acid detecting strips. The negative below is indistinguishable from a negative without vinegar syndrome.

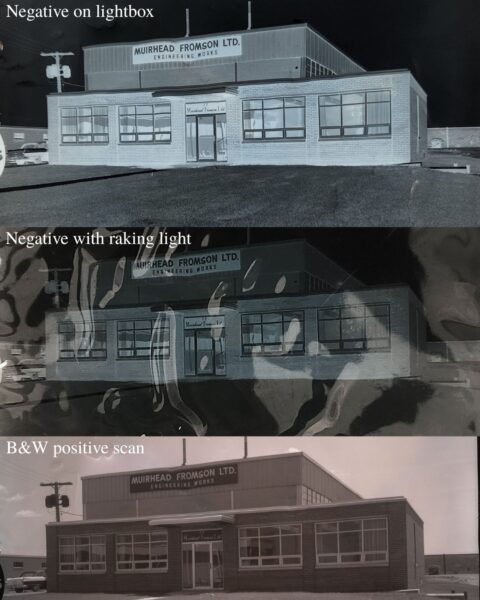

Stage two, where the film curls slightly and may have a slight smell of vinegar. The negative below was protected from curling due to being compressed in its original housing, however the raking light reveals some warping on the film base.

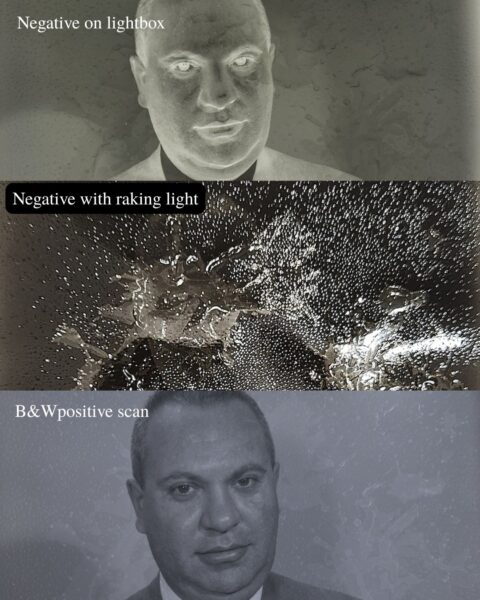

Stage three, where the smell of vinegar is present and the film begins to shrink, turn blue or pink, and becomes brittle. The negative below smells strongly of vinegar, has turned a deep shade of blue, which scans positively as orange, and has some ridges in the film base.

Stage four, where the film begins to warp and the smell of vinegar is strong. This negative has a slight blue tinge, raised ridges in the film base, and is much more brittle than the previous three, making it difficult to handle.

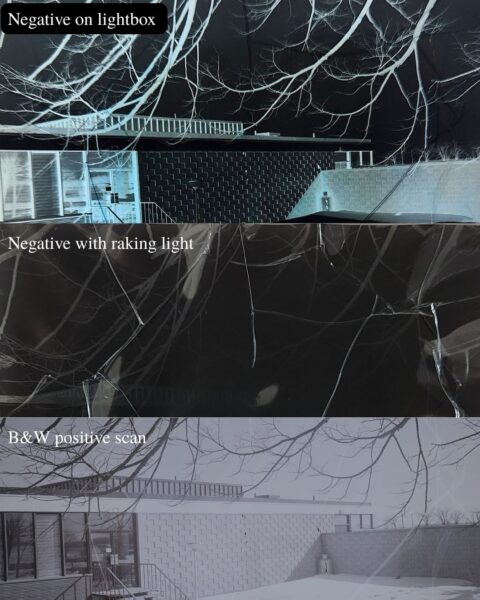

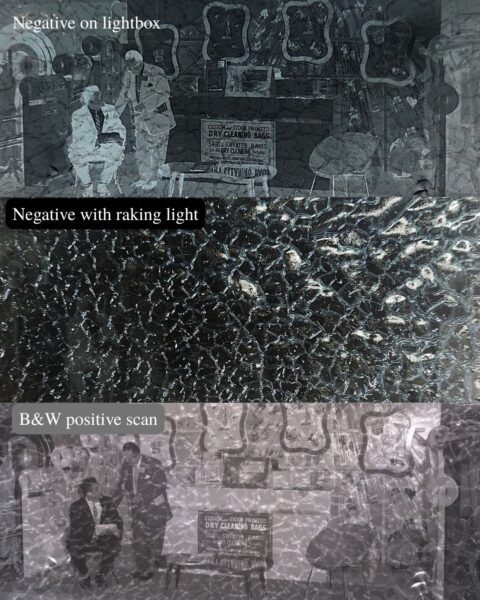

Stage five, where bubbles and crystalline deposits begin to form. This negative is dotted with hundreds of crystal deposits which compromise the image quality.

And finally, stage six, where the image may not be visible and channels form on the emulsion and film base sides. The image on this negative is still legible, but its quality has been drastically affected by the web-like channels, and crystal deposits.

Upon first glance, one may find a strip of curling, discoloured film to look quite insignificant, but each negative is a fragment of a larger story. Many of these images capture moments that shaped individuals, communities, and entire eras. Without timely preservation, these images, prone to silent deterioration, can vanish, erasing moments that once meant the world to someone. Caring for a personal collection of negatives does not have to be complicated or expensive, and a little effort can go a long way when it comes to saving photographs for decades to come.

An at home guide to preserving cellulose acetate film

To begin with, the easiest step to taking care of your negatives is handling them as little as possible. Our touch leaves oils from our skin on materials which can exacerbate their deterioration. Utilizing nylon, nitrile, or cotton gloves are best practice for handling photographic negatives, however freshly washed hands are also appropriate in a pinch. Boxes, mat board, and polyester or polyethylene sleeves can also be used to buffer negatives from heat and moisture as well as to prevent mechanical damage such as scratches and tears. Chemically stable materials (for example: cotton rag or chemically purified wood pulp) such as mat board, boxes, and file folders are also helpful for buffering from moisture. All photographic materials, especially negatives, should be mounted using non-invasive techniques. Instead of adhering an image to paper, consider using photo corners.

All photographic materials are also susceptible to deterioration from exposure to heat and humidity, but acetate film is especially prone due to its tendency to develop vinegar syndrome. Storing negatives in a basement or attic may seem like a good way to keep boxes out of the way, but these humid places with little temperature control can be a disaster for your negatives. Storing your negatives in a dry, cool place can prevent or slow down the onset of vinegar syndrome. Acetate negatives should also be stored away from incandescent lights, windows, doors, radiators, heating ducts, skylights, and exterior walls. If a humid area is the only place available for storage, consider purchasing a dehumidifier to keep your negatives dry, and if you wished to go even further, lining a cabinet with silica gel or desiccated mat board can also help moderate humidity fluctuations.

While all of these methods can drastically extend the lifespan of your negatives, reformatting them is the only way to ensure the image outlasts the negative. Photographing or scanning your negatives and uploading them to a hard drive not only preserves what is depicted in the negative, it also offers the opportunity to dispose of any negatives that you may not be able to take care of, thus creating physical space for photographs in better condition.

For a more general guide discussing the care of a wide variety of photographic materials, check out our previous blog post: Caring for your Family Photograph Collection.

How we take care of negatives with vinegar syndrome at A&SC

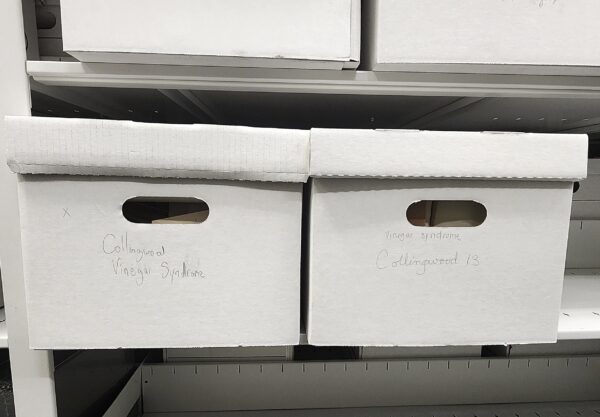

The first preservation step that is taken is isolating any film that may or may not have vinegar syndrome. This is due to vinegar syndrome’s tendency to spread to materials it is in close proximity with. Using the Collingwood collection as an example, any negatives with noticeable signs of deterioration were placed into separate boxes labelled “Vinegar Syndrome” until they are ready to be catalogued and housed.

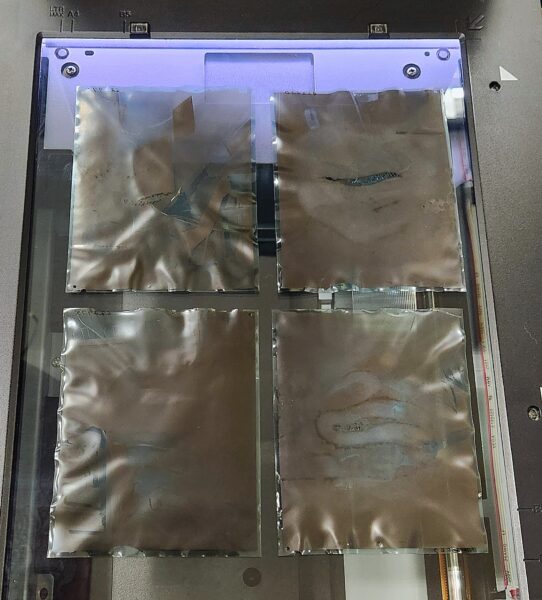

Each file is given a brief condition report specifying what stage of vinegar syndrome it is at before each negative is digitized. Due to their fragile nature, film holders can not be used to hold the negatives in place on the scanner and the negatives are instead carefully placed on the flatbed with some space between each other.

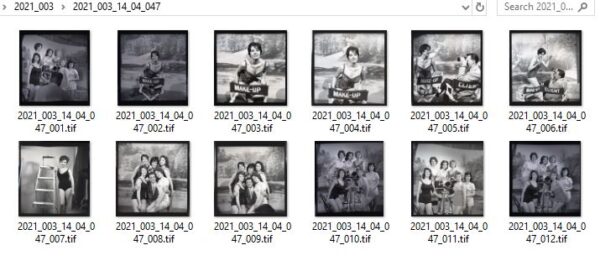

We scan images as TIFF files, which are the archival standard due to their lossless compression preserving more image data. Digitization is beneficial for a number of reasons including keeping track of object condition, lowering the amount of times the negative needs to be handled, and keeping the images accessible to staff and researchers even once they are in cold storage.

Once digitized, the negatives are slipped into archival quality plastic negative preservers where they are then placed into a file folder indicating its reference number, title, and year of creation. A stack of around sixty files, approximately 240 negatives, can fit into one legal-sized document box. Once a box has been filled, it is ready to be packaged for cold storage.

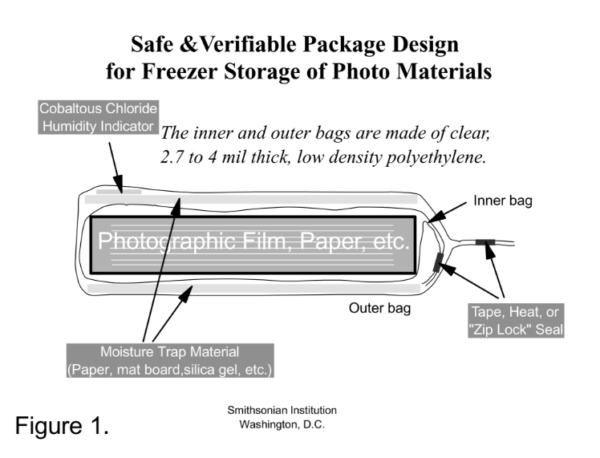

Cold storage slows vinegar syndrome by reducing the mobility of acetate ions and moisture in the film base, effectively putting the degradation process on pause. “It is important to note that cold storage cannot reverse the effects of vinegar syndrome, it only arrests further deterioration. Packaging the boxes correctly is incredibly important because their packaging needs to be semi-permeable to prevent moisture buildup. Any moisture that collects within the box and plastic will ultimately worsen the degradation of the negatives, and freezers, especially ones with high traffic, tend to be moist. The packaging method we use is the Mark McCormick-Goodhart Critical Moisture Barrier method, which utilizes two layers of low-density polyethylene, as well as a layer of four-ply desiccated mat board and a cobalt salt card placed between the polyethylene.

The polyethylene provides a semi-breathable wrapping, while the mat board acts as a moisture trap between the two layers of plastic. The cobalt salt card indicates the humidity percentage within the individual package by turning blue when exposed to moisture. We have one standing freezer and one chest freezer that are both kept around -12° Celsius, which is well within an acceptable range, however it should be noted that standards outlined by the Image Permanence Institute suggest that -18° Celsius and a relative humidity between 20 and 30 percent are ideal for negatives in cold storage. In an archive, achieving perfect conditions is often a balance of institutional resources and preservation priorities.

It is important to remember that cold storage is not the end of the preservation process, it is a long-term strategy to stabilize fragile materials. Once negatives are sealed in cold storage, we limit access to the physical object, offering the digitized copies instead, which minimizes the need for future handling. This ensures that even if a researcher is working with the material years from now, the original has not degraded further due to mechanical stress or temperature fluctuation.

Though vinegar syndrome may not stalk its victims like a monster from the shadows, its silent spread is just as chilling. The damage may seem invisible at first, but its impact is irreversible. Whether in a shoebox under the stairs or a meticulous archive, photographic negatives hold irreplaceable glimpses into the past. With just a few thoughtful steps, anyone can help stave off this creeping decay. So the next time you find yourself in a basement holding a box filled with old film, take a moment to ask yourself: “Is that just the damp smell of a basement, or is that the scent of vinegar in the air?”

If you are curious to see what vinegar syndrome looks like up close, come and visit the fourth floor of the library where our display windows outside the reading room feature real acetate negatives from the Collingwood collection in various stages of deterioration.

Bibliography

Amidon, Audrey. “Film Preservation 101: Why Does This Film Smell like Vinegar?” National Archives and Records Administration, June 19, 2020. https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2020/06/19/film-preservation-101-why-does-this-film-smell-like-vinegar/.

“A Visual Glossary of Six Stages of Acetate Film Base Deterioration.” Bibliotheque et archives Canada / Library and Archives Canada. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/collection/engage-learn/publications/ebooks/Pages/visual-glossary-acetate.aspx.

Brockbank, Nicole. “When Librarians Smelled Vinegar, They Knew the Clock Was Ticking to Save Historic Archives.” CBCnews, August 21, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/vinegar-syndrome-acetate-film-1.6939032.

Hill, Greg. “Caring for Photographic Materials.” Government of Canada, December 14, 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/preventive-conservation/guidelines-collections/photographic-materials.html.

McCormick-Goodhart, Mark H. On the Cold Storage of Photographic Materials in a Conventional Freezer Using the Critical Moisture Indicator (CMI) Packaging Method, 2003. http://www.wilhelm-research.com/subzero/CMI_Paper_2003_07_31.pdf.

Reilly, James M. “IPI Storage Guide for Acetate Film.” Image Permanence Institute, 1996. https://s3.cad.rit.edu/ipi-assets/publications/acetate_guide.pdf

“Vinegar Syndrome.” National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Accessed July 31, 2025. https://www.nfsa.gov.au/preservation/preservation-glossary/vinegar-syndrome.