The trend of portraiture rapidly evolved after the birth of the medium of photography. With this new and fascinating technology it became a novelty to have your photograph made and to use it as a symbol of personal identity. Through image content and format, a photograph can tell many things about its subject such as class, position, time period and personal values. With the first internal-combustion engine patented by Karl Benz in 1896, the rise of the automobile commenced and its increasing presence in photography is representative of the role it played in society during that time.

![Figure 1: 2008.001.221 William Lees, [Family group sitting in a studio car prop], cabinet card [between 1898 and 1914], Portobello, Scotland, 16.4 x 10.3 cm., image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2014/12/2008_001_221_001_web-600x388.jpg)

The presence of the automobile in this cabinet card (figure 1), made at a photography studio in Portobello, Scotland, suggests a general excitement for the ever increasing popularity of this new method of transportation. William Lees, a photographer known for his unique and entertaining studio backdrops, captured this family in front of a painted landscape where they are positioned around and inside of a painted studio prop car. Although this may have created an image that seems somewhat comedic to modern day viewers, the inclusion of this horseless carriage, even as a painted cardboard cut-out, speaks to the values and studio practices of the time period.

W. Lees has paid attention to popular recommendations for photography studio backdrops that encouraged photographers to approach the background of their composition with “as much attention as would an artist painting a picture.”[i] For instance, he painted this backdrop with gradation, creating depth complimentary to the presentation of his subjects. However, whether Lees has approached the Leonardo da Vinci level of natural authenticity desired by contemporary Henry Peach Robinson is left open for debate. As stated by the pioneer of combination printing, “be the figures ever so good, their effect may be seriously injured by ineffective support.”[ii] Lees’ use of the car prop also may not reach Robinson’s standards for accuracy, as although Robinson encouraged the photographer to pursue the use studio props outside of conventional columns and curtains, he warned that to do so is a fine art “in which departure from truth becomes absurd.”[iii]

Regardless of the quality found in the studio backdrop and props, W. Lees was working at the request of a customer desiring to be photographed in this specific way. What would have motivated a family to want their professional portrait taken in a makeshift cardboard car placed in front of a landscape backdrop that it does not quite fit into? Through the 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century, cars were a luxury that only the wealthy could afford to buy and maintain.[iv] They were a symbol of status and more of a plaything than a practical method of transportation. At the same time, they were new and increasingly accessible inventions that were readily gaining popularity in the U.K. throughout the late nineteenth-century. That a Scottish family such as that in figure 1 would have been eager to take part in this cultural experience, or even a makeshift version of it, is not a surprise.

![Figure 2: 2008.001.1821. Unknown, [Group portrait with a car], tintype [ca. 1905], 8.5 x 6.5 cm., image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2014/12/2008_001_1821_001_web-600x458.jpg)

Seen in this tintype (figure 2) is another example of a group choosing to sit within an automobile for their studio portrait. Although the photographer is unknown, the painted backdrop and presence of an actual car suggest the importance for this group to own a photograph documenting themselves within it. Generally, America had adopted the automobile by 1899, but it was still a novelty few were fortunate to own, an estimated 2500 produced in the United States that year for a population of approximately 74.5 million.[v] Perhaps the photographer was a travelling one, as many tintype studios were, and set up their backdrop outdoors allowing the inclusion of a real automobile to be a plausible option. Regardless of how it got there, its presence in this photograph makes a statement to the growing interest in this new machine.

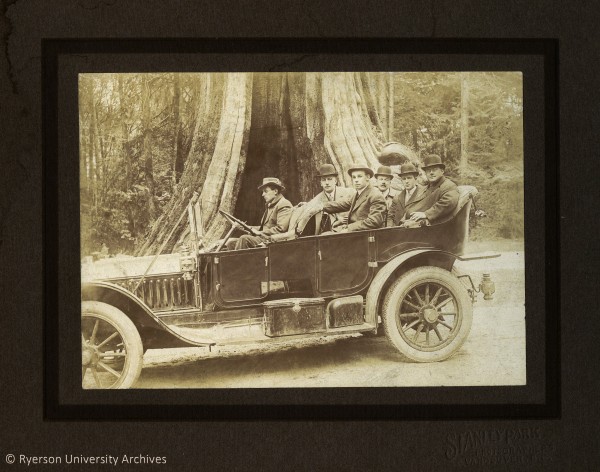

![Figure 3 (above): 2009.005.026. Stanley Park Photographers, [Group seated in a car in front of the Hollow Tree in Stanley Park], gelatin silver print on card mount [ca. 1910], Vancouver BC, 20.2 x 25.4 cm (with mount).Figure 4 (below): 2008.001.622. Stanley Park Photographers, [Portrait of men in car at Stanley Park], gelatin silver print on card mount [ca. 1915], Vancouver BC, 22.0 x 26.7 cm (with mount)., image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2014/12/2009_005_026_001_web1-600x478.jpg)

Figure 4 (below): 2008.001.622. Stanley Park Photographers, [Portrait of men in car at Stanley Park], gelatin silver print on card mount [ca. 1915], Vancouver BC, 22.0 x 26.7 cm (with mount).

These two portraits (figures 3 and 4), taken in front of the Hollow Tree in Vancouver, B.C., illustrate the role of the automobile and photography in tourism. Between 1900 and 1910 considerable progress was made in North American automobile production and automobiles were surpassing speeds of 25 kilometers per hour. Owning an automobile provided not only an opportunity to show off your wealth, but also an efficient way to travel through the countryside. No longer requiring the long set-up of horse and carriage, groups and families could spontaneously decide to take their car out to see sites and landmarks such as the Stanley Park Hollow Tree.[vi] Here we see the results of when these lucky travellers were met with a strategically placed camera in front of the Western Red Cedar tree, where a photographer was ready to snap a picture and document their visit.

![Figure 5: 2008.001.1471. Unknown, [Men in car], gelatin silver print on card mount [ca. 1910], United States, 25.5 x 30.6 cm (with mount)., image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2014/12/2008_001_1471_001_web-600x456.jpg)

As the introduction of the Kodak Brownie camera in 1900 provided the masses with an easy and inexpensive method of making their own snapshot pictures, professional photographers also found an increased mobility in their practice. Moving towards the 1920s, the increasing commonplace of photography was mirrored by that of the automobile, increasing the likelihood of seeing a car parked in front of your neighbour’s house. Combined, the presence of cars in photographs became more frequent and less formal. Groups and individuals were photographed in their cars at events, at their homes and anywhere else their car could take them (figures 5 and 6).

![Figure 6: 2008.001.1482.2. Unknown, [Portrait of two men in a car], gelatin silver print on card mount [ca. 1905], 24.8 x 30.5 cm (with mount)., image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2014/12/2009_005_1482_2_001_web-600x467.jpg)

The phenomenon of including an automobile within portrait photographs is not restricted to the early twentieth century. Cars, trucks, vans, motorcycles, RVs and ATVs are still among our most expensive and prized possessions and it is not unusual to desire a picture taken of ourselves with it. However, as technology changes, so too does the appearance of the vehicle we are sitting in (or standing beside), the ease at which we can acquire such an image, and the format in which we capture and display it.

![Figure 7: 2005.001.06.03.006. Unknown, Kodak Canada Inc., [Vehicles], gelatin silver print [ca. 1910], Toronto ON, 20.32 x 25.4 cm., image](https://library.torontomu.ca/asc/files/2014/12/2005_001_06_03_006_web-600x438.jpg)

If you have any additional information about these photographs or the automobiles in them, we would love to hear from you!

Special Collections, located on the fourth floor of the Ryerson Library, holds numerous examples of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century photographs, including cabinet cards, cartes de visite, tintypes, daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, as well as contemporary guidebooks and manuals. To access Special Collections give us a call or send us an email to book an appointment at: asc@ryerson.ca or 416-979-5000 ext. 4996.

Notes

[i] W. Whitehead, “Home-made Backgrounds,” The Photo-American, Vol. 3, no. 3 (January 1892): 70.

[ii] Henry Peach Robinson, Pictorial Effect in Photography Being Hints on Composition and Chiaroscuro for Photographers, (1869. Reprint, Pawlet, Vermont: Helios, 1971): 102.

[iii] Ibid., 106.

[iv] John Heitmann, The Automobile and American Life, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009): 10.

[v] James J. Flink, America Adopts the Automobile, 1895-1910, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1970): 29.

[vi] George S. May, A Most Unique Machine: The Michigan Origins of the American Automobile Industry, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1975): 42-45.

Bibliography

Flink, James J. America Adopts the Automobile, 1895-1910. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1970.

Heitmann, John. The Automobile and American Life. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009.

May, George S. A Most Unique Machine: The Michigan Origins of the American Automobile Industry. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1975.

Neal, Avon. “Folk Art Fantasies: Photographers’ Backdrops.” Afterimage. Vol. 24, issue 5 (March/April 1997): 1-13. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (9703172176).

Roberts, Peter. A Pictorial History of the Automobile. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1977.

Robinson, Henry Peach. Pictorial Effect in Photography Being Hints on Composition and Chiaroscuro for Photographers. 1869. Reprint, Pawlet, Vermont: Helios, 1971.

Thomas, Alan. The Expanding Eye: Photography and the Nineteenth-Century Mind. London: Croom Helm Ltd., 1978.

The Studio. Edited by Jerry Korn. New York: Time-Life Books, 1971.

Vogel, Dr. Hermann. “Filling the Picture. Accessories and Backgrounds.” Handbook of the Practice and Art of Photography. 2nd ed. Translated by unknown. Philidelphia: Benerman & Wilson, 1875.

Whitehead, W. “Home-made Backgrounds.” The Photo-American. Vol. 3, no. 3 (January 1892).

Wilson, Edward L. “Lesson K. Accessories and Light.” Wilson’s Photographics: A Series of Lessons, Accompanied by Notes, On All the Processes Which are Needful in the Art of Photography. New York: Edward L. Wilson, 1881.