The History and Growth of Travel Photography

Not long after the announcement of L. J. M. Daguerre’s daguerreotype process in 1839, the photographic medium and its technologies began to develop rapidly. While the unique image of a daguerreotype was well-suited to decorative portraiture, the lack of a negative and long exposure times made the process less profitable for landscape or travel photography since photographers could not reproduce multiple prints to sell to the public. As photographic technologies advanced, the invention of tintypes helped to lower the price of photographs by producing images on affordable metal plates, the sturdy nature of which also allowed for them to be shipped or mailed abroad. The increased use of the “wet-plate” negative process in the mid-nineteenth century allowed photographers to make multiple, saleable prints from one negative and thus became one of the more profitable processes for a travelling photographer despite the process’s cumbersome nature.

It was not until the invention of the Kodak camera in 1888 that photography truly became a popular hobby. Persuaded by the company’s slogan, “You push the button and we’ll do the rest”, consumers embraced the newly accessible nature of photography which no longer demanded the knowledge and technical skills as had been previously required.

While it was not until the last quarter of the nineteenth century that photography fell into the hands of the general public, photographers had long since been documenting exotic places abroad, returning with images that allowed citizens in their home countries to become familiar with far-away, foreign places despite having never left their hometown. Early photographers** known for doing so include Francis Frith, Maxime du Camp, J. P. Sebah, and Samuel Bourne, to name just a few.

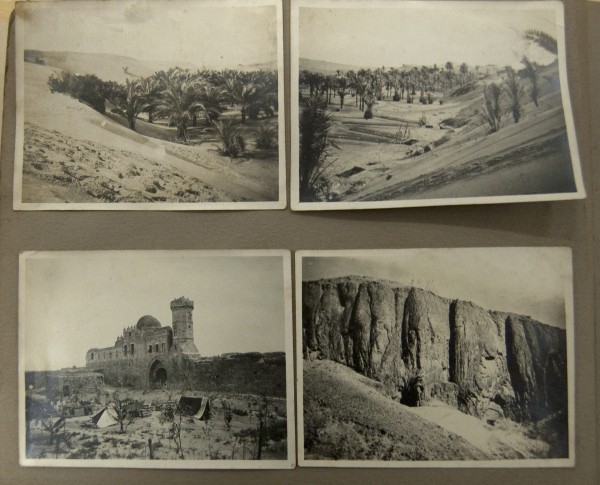

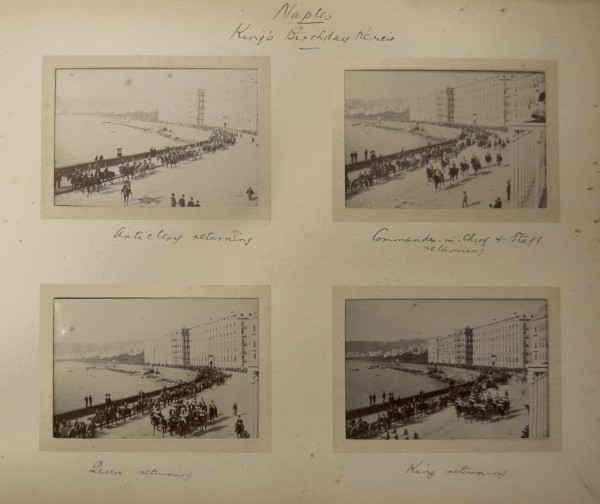

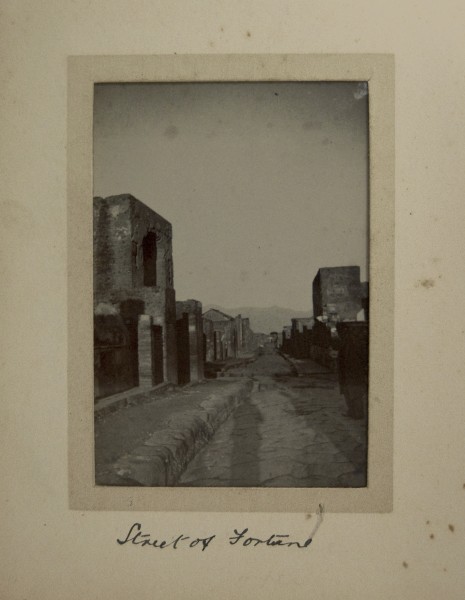

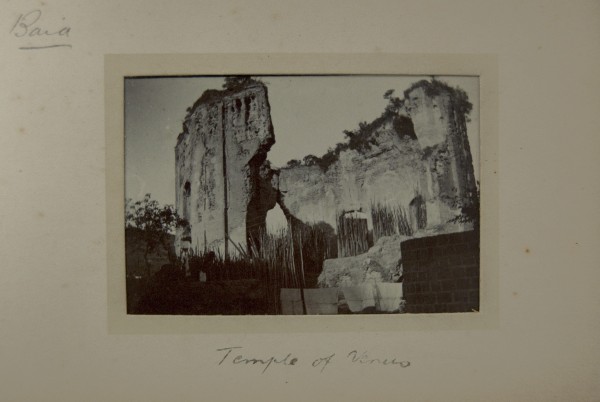

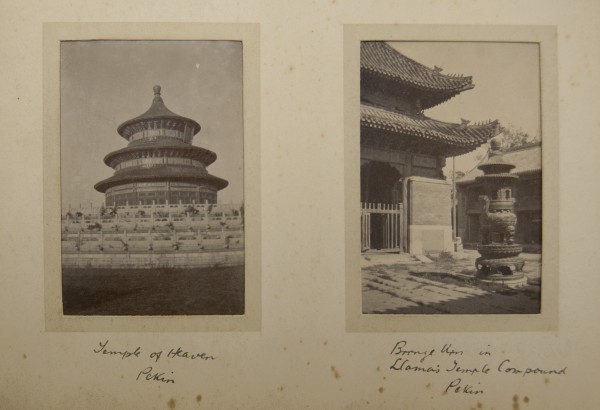

As travel methods advanced and became more readily accessible, people carried their own cameras and documented their travels, returning home to brag to friends and relatives about where they had been, presenting their photographs as proof of their exotic experiences. It is these types of photographs that we find in the Lorne Shields fonds. Containing photographs of scenic landscapes, major sites of attraction and other tourist snapshots, we can explore countries not only half way around the world but also as they existed over a hundred and fifty years ago.

Today, travel photography remains popular as ever as both cameras and global travel become increasingly accessible to the public. Tourists now scramble to get photographs of themselves at whatever landmarks are deemed “must-sees” in their respective destinations, with the infamous “selfie” becoming a dominant sub-category in travel photography. While the photographic medium has improved exponentially since its conception, we must be wary of our recent addiction to the accessibility and instantaneity that digital photography – particularly cell phone photography – continues to provide us with. In light of our haste to document and communicate our travels, we must pause to consider a concern that many have started to address: at what point are do we sacrifice our genuine appreciation of the travel experience in order to prove our being there, as we increasingly spend more time producing or interacting with these “proof of experience” photographs than with the actual landmark or destination itself.

Travel Photography in the Lorne Shields Fonds

Best known as an avid bicycle collector and historian, Lorne Shields’ interest in collecting began at an early age when he observed – and later helped to operate – his father’s business, selling bicycles and various parts and accessories. Though his initial interest was primarily focused on acquiring bicycle-related objects and memorabilia – such as photographs, books and magazines–, his passion for and dedication to collecting soon expanded. Photography became one of his many collecting interests and in 2007 he donated part of his photographic collection to Special Collections at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Library.

Comprised of boxes of photographs, textual materials and photographic albums, the Lorne Shields Fonds includes a variety of photographic material including studio portraiture, landscape photography, and many amateur snapshots, and almost half of the photographic albums are titled after countries or travels abroad.

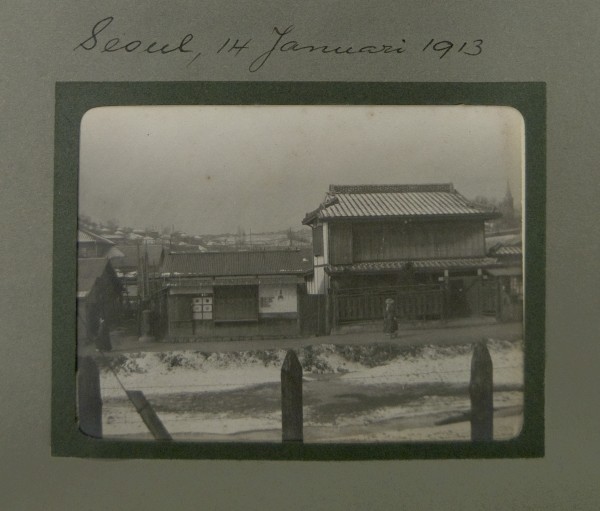

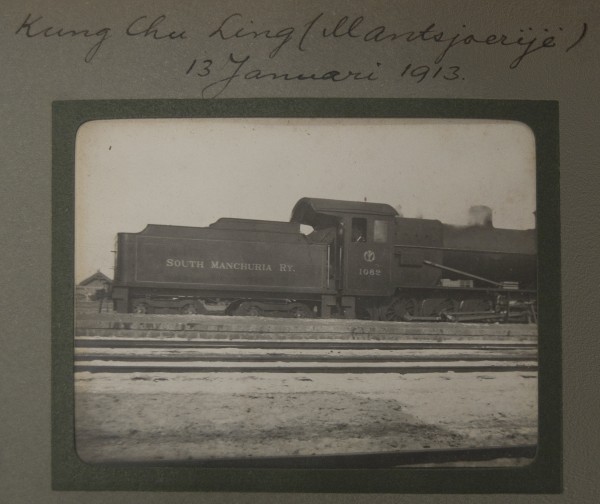

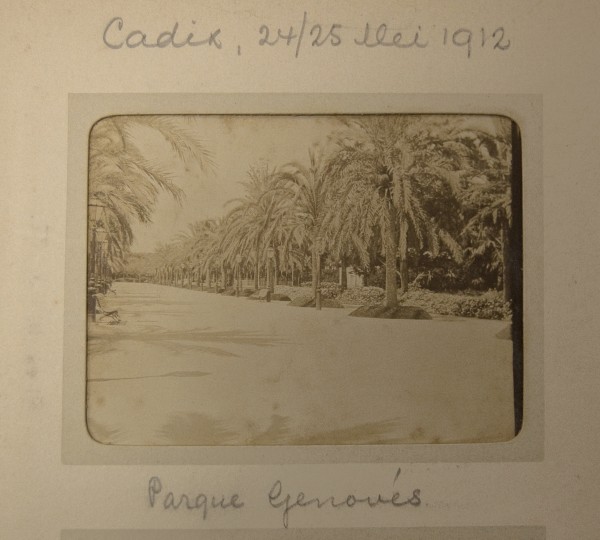

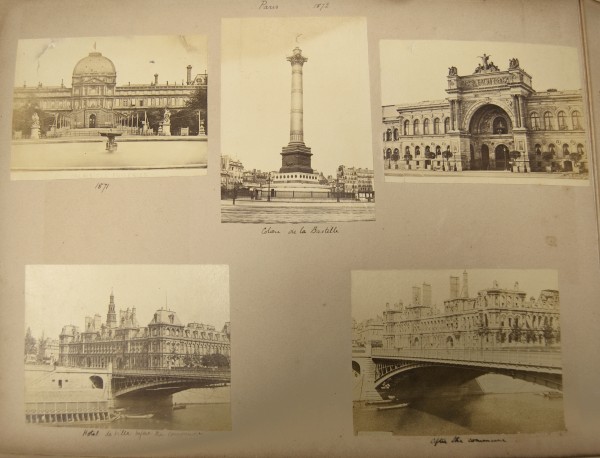

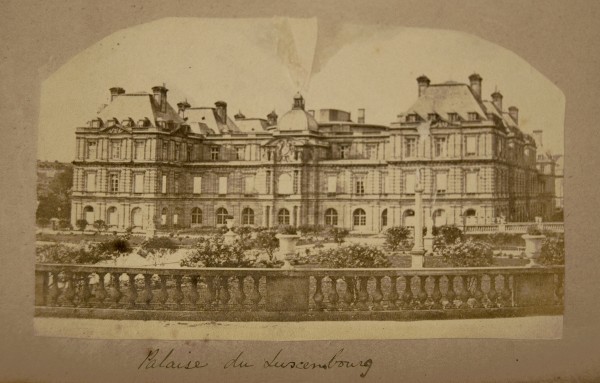

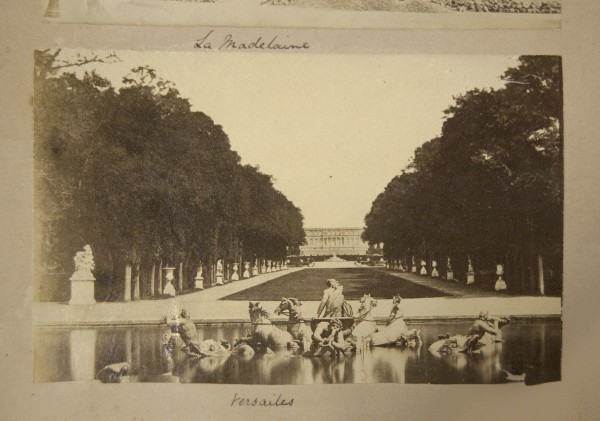

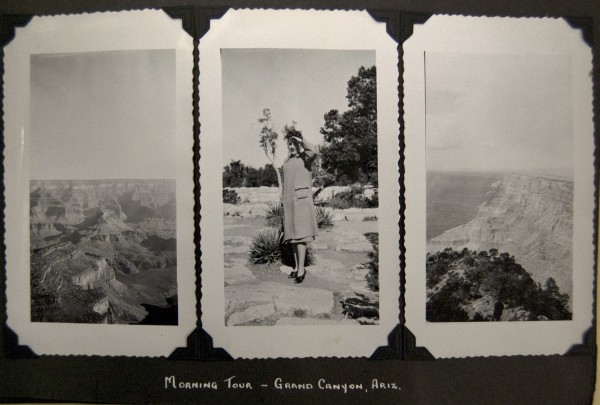

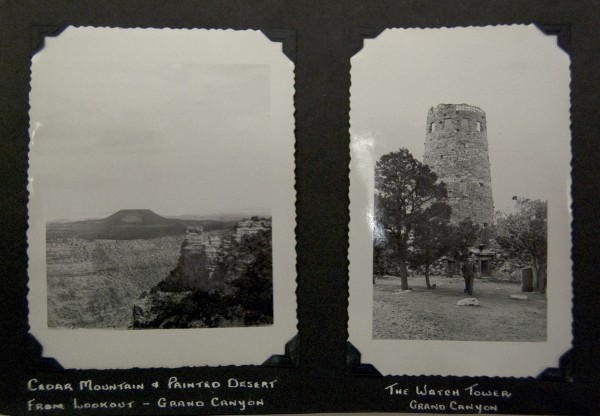

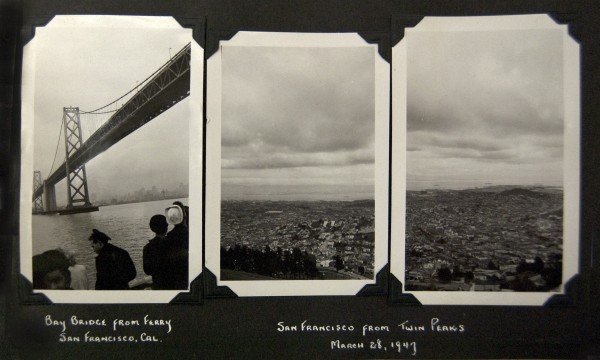

These travel albums consist of photographs primarily from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and include photographs taken in Italy, France, Spain, Sweden, England, Morocco, Malta, Korea and many other countries. Photographs of well-known landmarks and tourist attractions include sites such as Place de la Concorde in Paris, France; Plaza de Isabel II, Spain; The Leaning Tower of Pisa, Italy; the Temples of Venus, Mercury and Jupiter in Rome, Italy; various locations in the Grand Canyon, in Arizona, U.S.A; and many more. Below is a small selection of the vast number of images in the fonds that address photography’s use in documenting travel in the late nineteenth and early to mid- twentieth centuries.

Conclusion

Almost since the beginning of photography’s existence, photographers have been documenting their travels in foreign countries abroad. Improvements in photographic technologies made travel photography increasingly profitable for photographers until the invention of the Kodak camera in 1888, which granted widespread accessibility to photography for the general public and led to an abundance of scenic landscape and tourist snapshots as individuals documented their travels across the globe.

The Lorne Shields Fonds presents numerous travel photographs in many of its photographic, documenting several countries and well-known sites in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These photographs represent a specific type of photography at a specific point in time. Today, this type of photography – travel photography – is increasingly affected by the instantaneity possible with digital and cell phone photography, allowing photographs be shared literally moments after they are created. It is this instantaneity that we must be wary of, as many begin to worry that the perceived importance of sharing these images immediately may detract from the experiences of travel itself.

References

British Library Online Gallery, curator. (n.d.) The World in Focus. In Historic Photographs. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/photographicproject/worldinfocus.html

British Library Online Gallery, curator. (2009). Travel. In Points of View. Retrieved from: http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/pointsofview/themes/travel/index.html

Flemming, J. (April 1st, 2012). From Boneshaker to the Pneumatic Tire. Ornamentum. Retrieved from: http://ornamentum.ca/article/from-boneshaker-to-the-pneumatic-tire/

Francis Frith. In George Eastman House Still Photograph Archive. Retrieved from: http://www.geh.org/ne/mismi0/frith-sin_idx00001.html

Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Collections. Retrieved from: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/the-great-sphinx-at-giza-looking-southwest-334699

Research Photographs at Princeton University, curator. (n.d.). Global Views: Nineteenth Century Travel Photographs. http://www.princeton.edu/researchphotographs/exhibitions/

Sandweiss, M. A. (2006, Winter). Photography in Nineteenth-Century America. History Now 10. Retrieved from: http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/art-music-and-film/essays/photography-nineteenth-century-america